Ecosystem maturity and the stepping stone strategy

Rita McGrath

One of the great puzzles in business is why some entrepreneurs benefit tremendously from the unfolding of a strategic inflection point, while others who “saw” it equally clearly disappeared into the mists of forgotten business lore. One explanation is that introducing even prescient innovations into an unripe ecosystem is as much a recipe for disaster as failing to innovate in the face of a pending inflection point. Being ahead of one’s time is as miserable as being too late.

James Moore, in a 1993 article, is often credited with popularizing the concept of a business ecosystem. Like a natural ecosystem, he suggested, businesses coevolve, with the actions of one influencing others, just as the change in one species affects the habitat and can provoke changes in other species. For our purposes, a business ecosystem can be defined as having a number of definable components.

There must be a source of energy and resources. Natural ecosystems are fueled by energy from the sun. Business ecosystems are fueled by flows of money and other resources. In a natural ecosystem, natural selection has led to differently abled creatures occupying them. In business, path-dependent learning and investment processes lead to firms with differential capabilities. There must also be a form of connective tissue between players in a business ecosystem. Unlike ecosystems in nature, however, connections between business entities have an element of sentience to them – human actions and decisions determine flows of communication and commitment. This in turn creates interdependencies – the actions of one connected party affects others. Finally, business ecosystems must have regimes for regulating access and ownership of resources. Depending upon the extent that each of these components functions effectively, a business ecosystem can be said to be more or less mature.

A strategic inflection point consists of what Andy Grove called a 10X shift in the forces that affect a business. As he pointed out, such a change represents a technological transition in which an older regime is in the process of being replaced by a newer one. If a business is prepared to navigate such a transition, by retiring older technologies, embracing newer ones, and transitioning their activities, an inflection point can represent a valuable opportunity for growth. It can also presage a decline in business as older ways of doing things are replaced with new ones and revenues erode accordingly.

Phase changes

There are four states with respect to the emergence of a strategic inflection point, with differing ecosystem implications. These are consistent with Gartner’s hype cycle. This order is typical: hype, dismissal, emergence, and post-inflection maturity. Each phase has ecosystem implications depending on the incentives and motivations of the various participants in it.

The recognition that an inflection point is underway is often accompanied with a fair amount of hype, particularly if early participants fuel interest in future riches to be had. Entrepreneurs start businesses, investors put in money, and journalists enthuse about the thing that is going to transform economic life as we know it for all time. Speculators often cause the value of underlying assets to inflate wildly, creating a modern-day version of Dutch tulip mania. The fanfare surrounding bitcoins in the mid-teens is a classic example of the excesses of this stage.

Like a Greek tragedy, the hype stage almost always ends in a bust – sometimes dramatically. This brings us to the dismissive stage in the lifecycle, in which those who sat out the hype take an “I told you so” perspective, saying “that’s never going to happen.” This stage, however, is often where the real opportunities lie. In the dismissive stage, a few of the initial entrants will have survived the shakeout and begun to set the foundation for major growth. They will be building viable business models, finding new customer needs to address and potentially even begun making money. This is the point at which toehold investments might make sense, seeding the emergence of a more “real” ecosystem than existed in the hype stage. Thus, with respect to bitcoin, establishment players such as JP Morgan, by 2019, were in trials to solve real business problems at scale for corporate clients.

Dismissal is often followed by a much quieter but more “real” emergent stage. At this point, those who are paying attention can clearly see how the inflection might change things. During this stage, critical decisions about infrastructure, ecosystem relationships, business models, and asset ownership are being made. This is the stage at which an organization should be taking out options, investing in ecosystem partnerships, and keeping on top of what the emerging business could be.

Finally, the inflection point comes into its own at the maturity stage, in which it is now obvious to everyone how it will change the world. Those who were not prepared see their businesses go into decline. Post-inflection, the change is incorporated into everyday life assumptions. By this point there are plenty of people who have completely forgotten what things were like before the inflection took place. Most players in an ecosystem have worked out relations among them, transactions are well understood, and business models are well in place.

Competing in arenas

Although strategic management theory for many years has embraced the idea that an “industry” represents the most important unit of analysis for strategic thinking, ecosystems as described above are blissfully unconcerned with industry boundaries. Indeed, recent developments have demonstrated that the most significant competition in many categories emerges from players from different industries. For instance, consider the woes of the dairy industry, which has seen a steady drop in the demand for cow’s milk, while makers of plant-based “milk” have seen skyrocketing demand. In theory, these are different industries. In reality, they compete.

Instead, we can use the concept of a competitive arena. An arena, like a natural ecosystem, consists of an environment in which resources are present. In business, this means a market, with customers who have money to spend. How customers spend their money will depend on what Clayton Christensen famously called their “jobs to be done.” Customers buy products and services to get jobs done in their lives. Different jobs compete with one another for urgency and salience, and different providers compete with one another for the total resource pool available. Thus, customers that value connectivity over, say, eating out at restaurants, will put their resources into buying cell phone minutes and not into fine dining. The restaurant and the cellular provider are actually competing with one another.

A strategic inflection point can change what is possible in the service of customers getting the jobs they would like to get done in their lives done. This is often what fuels the initial hype cycle. And yet, what many early entrants into a new ecosystem fail to realize is that brand-new ecosystems are often missing some component that would allow a complete job to be done. Until the ecosystem is mature enough, even though customers may be intrigued, ecosystem weaknesses stop them from making a consumption choice.

Perhaps a concrete example would be helpful. In 1964, AT&T unveiled the world’s first phone that combined voice and video. Called the AT&T Picturephone, it was shown at the company’s exhibit at Disneyland in California. The first attempt to sell the product commercially was in 1970, in Pittsburgh. It was hailed as a great advance that would revolutionize how we communicate. While people were intrigued at the concept, it was a hard sell. For starters, the company wanted to charge consumers $160 / month for phone rental (about $1,000 in today’s dollars). And for businesses, who might have been willing to swallow that kind of money, the phone’s features for things like document sharing and replacing face-to-face meetings were too limited to offer real benefits. After a $500 million investment in the project, it was discontinued in 1978.

Part of AT&T’s dilemma was that they were inhibited from investing to create an ecosystem around the phone - fear of having their monopoly broken up meant they didn’t cross-subsidize the technology with profits from elsewhere in the Without widespread adoption, they were unable to take advantage of network effects (I mean, if you’re the only person with a picturephone and there is no one else with one, it isn’t worth much). Today of course, we think nothing of video chatting and in a post-COVID-19 world have actually become dependent on the technology.

The lesson here is that it isn’t enough to invent great technology if the technology by itself can’t break through to become a customer’s preferred way of getting critical jobs done in their lives. And often, it is the absence of critical ecosystem players that prevent a satisfying conclusion to a job.

Ecosystem evolution: the stepping stone strategy

Missing an inflection point can be devastating. But moving too soon can leave a company stranded. As an alternative, consider an approach called the “stepping stone” strategy. In this strategy, right about the time an inflection point has passed through the hype stage, it makes sense to both take out some strategic options and look for a stepping stone opportunity. A strategic option is a small commitment made today to create the opportunity to make a future choice. Simply investing in the option does not commit one to following through on the entire commitment – it merely provides information and degrees of freedom about what is really going on.

Stepping stone options have several properties that are important from an ecosystem point of view. First, they represent a really important job to be done from the point of view of the customer. Second, the job is either not being done very well, or not being done at all. Third, the customer has resources to spend to get that job done or will divert resources from other demands to do so. Fourth, and most importantly, the complete job can be done with the technology as it is, with whatever rudimentary ecosystem exists at the time. This implies that a stepping stone option is designed to serve a niche market. While the markets may be small at the outset, they should support high margins – after all, if the job to be done is important enough, the customer should be willing to pay.

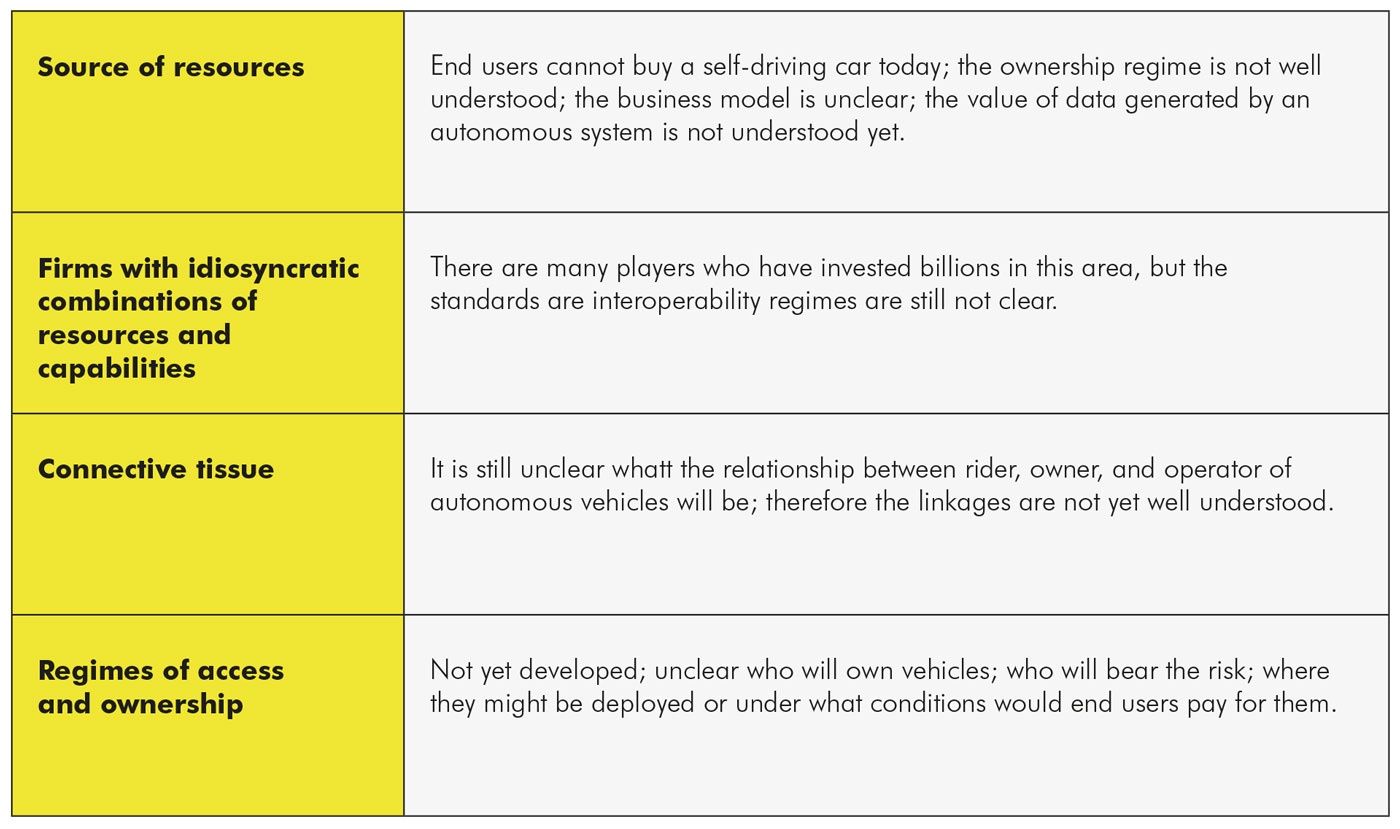

Let’s take the concrete example of autonomous vehicles. While the technology for autonomous driving is extraordinary, and very nearly good enough for drivers to trust it in many situations, other ecosystem elements are not yet mature. Consider our definition of an ecosystem as applied to this arena.

Given the gap between what a more mature ecosystem would look like and the present state of the art in autonomous vehicles, one might well question whether the massive investments made in the technology so far are likely to benefit the early movers.

And yet, there are fascinating examples of stepping stone strategies in this space. One involves the use of autonomous capabilities in military applications. An arena ripe for adoption is in the case of vehicles used in its resupply programme. Called the “Expedient Leader-Follower” programme, it consists of semi-autonomous functionality that nonetheless offers real benefits. Rather than, say, seven trucks in a convoy with the mission of supplying front-line troops, the technology is good enough for six trucks to play follow-the-leader while human beings in the lead vehicle make the kind of in-the-moment judgment calls that are difficult to pre-programme in an algorithm. The technology is already deployed in this manner, the developers are being paid and the military customers can put a real value on the benefit of keeping troops out of harm’s way while being able to use them for more productive activities.

Of course, this application is not large enough to justify the billions that have been spent on developing autonomous technology. It is, however, indicative of the kind of seed crystal that prompts the initial emergence of an ecosystem. Gradually, the applications served by the technology will expand as firms learn and the technology continues to improve. As it does, ecosystem leaders can use their vantage point to create a clearer roadmap for commercial applications. Eventually, such stepping stones can evolve into platforms to which others can link their capabilities to create even greater value for end users.

Ecosystem ripeness – a critical concept for strategy

This article has encouraged would-be innovators to proceed with caution when facing an abundance of enthusiasm at the growth prospects created by a strategic inflection point. While there is no harm in participating as an inflection point creates new possibilities, doing so in an early, complete-enough ecosystem is often more fruitful than rushing headlong into what could turn out to be an unrealized prize.

Rita Gunther McGrath is a professor at Columbia Business School, where she directs the popular Leading Strategic Growth and Change programme. She is the author of the best-selling The End of Competitive Advantage (Harvard Business Review Press, 2013) and Seeing Around Corners: How to Spot Inflection Points in Business Before They Happen (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019). She has written three other books, including Discovery Driven Growth, cited by Clayton Christensen as creating one of the most important management ideas ever developed. She is a Thinkers50-ranked thinker and previous winner of the Thinkers50 Strategy Award.