Project-based ecosystems

Antonio Nieto-Rodriguez

7th February 2014, 20:14, Fisht Olympic Stadium, Sochi, Russia: 2.1 billion people are watching Vladislav Tretiak, an all star ice hockey player, taking the Olympic flame from Maria Sharapova, and lighting the Olympic torch at the newly built stadium. The 2014 Winter Olympics Games are officially open. The state-of-the- art stadium is jam-packed with 40,000 sports enthusiasts. Sochi was selected as the host city in July 2007, during the 119th IOC Session held in Guatemala City. After seven years of work, Sochi is the capital of the world for the coming weeks.

Records have already been set. The stats are eye-watering1:

- Total budget: $2.5 billion

- Over 400 projects delivered with more than 28,000 milestones

- Nearly 9,500 purchase orders placed with contractors/suppliers

- More than 50,000 employees, volunteers and contractors

- 2,859 athletes from 87 countries

- 5,000 artists from 70 Russian regions

- 14 new modern venues (including 10 sport venues) and infrastructure built from scratch featuring a barrier-free environment for people with physical disabilities

- formation of a volunteer movement in Russia.

The Summer and Winter Olympic Games are among the largest transient ecosystems. Right after the hosting city is selected by the powerful International Olympic Committee, a colossal international multiskilled temporary and agile ecosystem is set up for the next seven years.

The Olympics is a project-based ecosystem. There are many others – think of putting a man on the moon in 1969, the creation of the double-deck Airbus A380, the introduction of the euro in 2001, and the rescue of the Chilean miners in 2010.

In this chapter we will explore the concept of mega projects as transient ecosystems, the benefits of these and how any organization can establish one. But before that, I will briefly set the context of what I call the Project Economy.

The rise of the project economy

We all have heard about the disruptions that are impacting our society and the business world: robotics, artificial intelligence, shared economy, blockchain, big data, and so on. But, there is one extreme disruption affecting our world that the media and academia have completely missed. For over 100 years, organizations have been run and structured in a very similar hierarchical way with power, budgets, and resources divided between departments, the so-called “silos.” Management and management theory was focused on how to run and optimize the business in the most efficient way. Projects were an addition, but hardly ever a priority.

Today, due to the speed of change witnessed in the past decade, this model has become obsolete. The

day-to-day running of a business will soon be carried out through automation and robots – and is already done so in many instances. Projects have become the essential part of any organization.

The quiet emergence of projects as an economic engine has been powerfully disruptive. Projects have become the essential model for delivering change and creating value. In Germany, for example, approximately 40 percent of the revenue generated by the nation’s companies can be attributed to projects.

McKinsey estimates that the world needs to spend about $57 trillion on infrastructure projects by 2030 to enable the anticipated levels of GDP growth globally2. Of that, about two-thirds will be required in developing markets, where there are rising middle classes, population growth, urbanization, and increased economic growth. These countries need infrastructure, but all too often many years will pass and the promised road, bridge, and metro projects still will not have materialized. Most of this $57 trillion will be spent and delivered as mega projects.

In most circumstances, a mega project can be seen as a temporary ecosystem: a composition of individuals, departments, organizations, companies, contractors, vendors, etc., that work together towards a common objective. Learning from each other, understanding the purpose of the project, working on the technical details, and finding solutions requires a steep learning curve and an ecosystem that holds all the knowledge together.

But let’s look at the definitions.

Project-based ecosystems. The concept of business ecosystems is not new, it has been a model embedded in our economic history. The large fairs in many medieval cities at which merchants came together and exchanged goods for a given period of time each year could be regarded as early forms of ecosystems. However, it is only in the past decade that the term “ecosystem” has established itself in the business world.

Traditional views on ecosystems refer to established and permanent bonds between companies and industries.

In most instances, this model is only accessible to large corporations who decide to establish an ecosystem that they largely or completely own most of the control of and in which they choose the partners.

But how about the small and medium enterprises, or the less glamorous corporations, or the temporary endeavours that our society needs to keep developing? How can they benefit from the positive aspects of ecosystems despite their size, resources, or brand limitations?

My proposal to them is to consider establishing a joint project. A project is a proven method of bringing ideas into reality. It has a purpose, aiming at solving a problem or creating something new. It is unique by nature – even if it has been done before, some elements will be different. A project requires a team of mixed skills and expertise and demands a project leader to drive the team. It is constrained by time (has an end date or finish line), budget (funds and resources), and design (ambition and quality). A project must address – often through intensive communication – individual, collective, and cultural behaviours (stakeholders).

According to BCG, a business ecosystem is a dynamic group of largely independent economic players that create products or services that together constitute a coherent solution, which applies precisely to large projects3. A business ecosystem has the following four characteristics, which can be validated from a project perspective:

Modularity. In contrast to vertically integrated models or hierarchical supply chains, in business ecosystems the components of the offering are designed independently yet function as an integrated whole. In many cases, the customer can choose from the components and/or how they are combined.

Projects have very little hierarchy – mostly two to three levels – which allows for quicker decision-making. They are composed of modules and phases which can be easily moved around according to the needs of the project and/or management.

Customization. In contrast to an open-market model, the contributions of the ecosystem participants tend to be customized to the ecosystem and made mutually compatible. This implies that participation in the ecosystem requires some ecosystem-specific investments.

Projects focus and build the implementation plans on the needs of the end customers; everyone working on that initiative will dedicate resources and competencies to addressing those needs.

Multilateralism. In contrast to open-market models, ecosystems consist of a set of relationships that are not decomposable to an aggregation of bilateral interactions. This means that a successful contract between A and B (such as phone maker and app developer) can be undermined by the failure of the contract between A and C (phone maker and telecom provider).

As we saw in the example of the Sochi Olympics, in a mega project there can be hundreds, or even thousands of partners involved. There is no room for individualism, people have to work together towards the common goal of the project.

Coordination. In contrast to vertically integrated models or supply chains, business ecosystems are not fully hierarchically controlled, but there is some mechanism of coordination – for example, through standards, rules, or processes – beyond a simple open-market mechanism.

Projects span years and decades – but there is always an end; they involve hundreds of companies – private, public, and non-profit – engaging thousands of individuals and often millions of individuals are impacted. Clear governance and coordination is the essence of projects and project management.

The benefits of projects as transient ecosystems

Besides the three main benefits of ecosystems – access to a broad range of capabilities, the ability to scale quickly, and flexibility and resilience – projects bring additional ones:

Common purpose and a clear deadline – increases focus and pressure. First, projects need to have a purpose shared by all the parties involved. In the case of the Olympic Games, for example, it is usually around demonstrating to the world that one’s city can host the greatest games ever. The purpose is shared, understood, and endorsed by most of the stakeholders. In addition, projects need a clear deadline, which will help increase the focus and the pressure to deliver on time There is no room for dragging on forever.

Cheaper to access – anyone that shares the purpose adds value. Project-based ecosystems are cheaper to access, and don’t require huge investment of capital or resources. As long as your organization can add value to the project and share the purpose, it is easy to start contributing.

More equal – doesn’t need to have a big corporation behind it.

Project-based ecosystems don’t need a big corporation behind them that drives the project. They are more equal. A project can be led by a small entity, or a joint consortium of small or medium size companies.

Easier to build trust – it’s easier to build trust in project-based ecosystems when the purpose is clear and shared, the benefits have been defined, and the contribution of each party has been defined.

Organizational learning is essential – one of the success factors of projects, and mega projects in particular, is learning and competencies building. The establishment of an efficient learning ecosystem is essential for the success of these gigantic projects.

Project Canvas for project-based ecosystems

The Project Canvas is a well-known framework based on research carried out on hundreds of successful and failed projects ranging from small individual to large-scale ones, and it can also be applied to transient ecosystems.

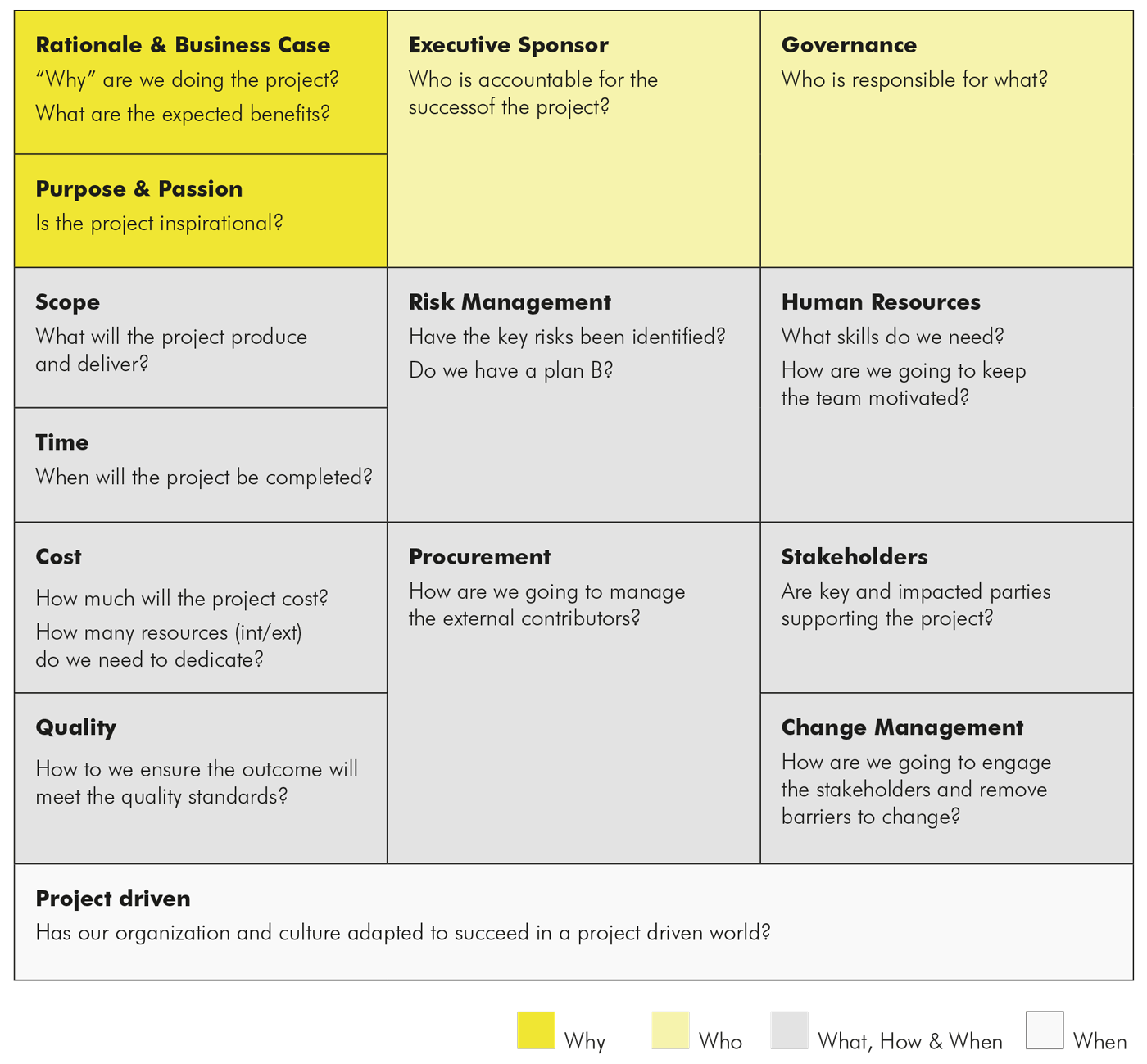

The framework can be used by leaders and organizations at the beginning of a project-based ecosystem to assess how well it has been defined and whether it is worth starting right away or needs further refinement. It is composed of 14 dimensions grouped into four major domains:

Domain 1: Why

The Why dimension covers the triggers and actual meaning of an ecosystem (the rationale and business case, and the purpose and passion), which will become the drivers once the project gets underway.

Rationale and business case: All ecosystems demand that projects always have a well-defined business case. Experience shows, however, that business cases have biases and subjective assumptions, especially concerning the financial benefits from the ecosystems, which often get inflated in order to make the endeavour seem more attractive to decision-makers. The business case has to be complemented with a clear purpose.

Purpose and passion: Besides having a rationale, a project should be linked to a higher purpose. Jim Collins and Jerry Poras, authors of Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies, provide a useful definition of “purpose,” which we can adapt as follows: “An ecosystem’s purpose is its fundamental reason for being. An effective purpose reflects the importance people attach to the project’s work – it taps their idealistic motivations – and gets at the deeper reasons for a project’s existence beyond just making money.”

Domain 2: Who

The Who domain relates to the executive sponsor and governance, and it addresses the elements of accountability and allocation of responsibilities.

Executive sponsor: Many ecosystems start without it being decided who is ultimately accountable for their successful delivery. As project-based ecosystems tend to have several leading executives involved, they are often prone to “shared accountability and collective sponsorship.” As a result, many executives feel responsible, yet no one is really accountable for driving the project to completion.

Governance: The executive sponsor, together with the project coordinator, should define and establish the ecosystem governance. The governance in a project is represented by a project chart in which the various contributing roles and decision-making bodies are defined.

Domain 3: What, How & When

The What, How & When domain covers the fundamental elements that constitute the project-based ecosystem. They can be split into technical areas and people-related elements.

Scope: Understanding and agreeing what the ecosystem will consist of and deliver – the scope – is one of the raisons d’être of projects. Other terms for scope include specifications, detailed requirements, design, and functionality. The scope is the most important element in making an accurate estimation of the cost, duration, plan, and benefits of the project-based ecosystem.

Time: Time is one of the major characteristics of project-based ecosystems in that, unless there is an articulated, compelling, official, and publicly announced deadline, there is a good chance that the project will be delivered later than originally planned. Delays in projects mean, besides extra costs, a loss of benefits and expected revenues, both having a tremendous negative impact on the business case of the initiative.

Cost: Budget in project-based ecosystems is composed mostly of the time dedicated by the project resources. These mainly include the people working on the project plus all other investments (consultants, material, software, hardware, etc.) required to develop the scope of the project.

Quality: Ensuring that the outcome of the project-based ecosystem meets the quality expectations is an integral part of projects, yet it is often overlooked or not a priority. Often teams focus on doing the work and leave the quality and testing part to the end of the project, when adjustments are most expensive.

Risk Management: Risk management is one of the most important techniques in project-based ecosystems. Bluntly, if a project fails, it is because the risks that caused the failure were either not identified or not mitigated on time by the project team.

Procurement: Project-based ecosystems require resources, input, and material from hundreds of different parties. Establishing and respecting procurement processes is essential to the success of these kinds of projects.

Human Resources: Project-based ecosystems require pulling and leading resources across different organizations often across different regions. It is critical to create high performing teams, where everyone has a role to contribute and is recognized for that.

Stakeholders: Project-based ecosystems have hundreds of stakeholders, who are individuals and groups (entities, organizations, etc.) that are impacted by, or who impact, the project. The more stakeholders, the more efforts required in terms of communication and change management activities.

Change Management: Aim to communicate what needs to be done clearly and accurately, ensuring that everyone involved is ready to embrace the changes introduced by the project-based ecosystem.

Domain 4: Where

The Where domain covers the external elements that can have a positive or negative impact on the ecosystem.

Project-Driven Organization: It is important the project-based ecosystem is a priority for the environment for which it will be implemented. For example, the Olympic Games is a top priority for the country and government that hosts it. This priority allows the allocation of sufficient resources, competencies, and attention that leads to the success of the project.

If we look at projects and mega projects as agile ecosystems, and learn from them, we will understand that there is a new way of improving the efficiency and impact of this model.

Antonio Nieto-Rodriguez (antonionietorodriguez.com) is a leading expert on project management and strategy implementation, and was recognized by Thinkers50 with the 2017 Ideas into Practice Award. He is the author of Lead Successful Projects (2019, Penguin), The Project Revolution (2019, LID), and The Focused Organization (2012, Gower). He has held executive positions at PricewaterhouseCoopers, BNP Paribas, and GlaxoSmithKline. Former chairman of the Project Management Institute, he is the cofounder of the Strategy Implementation Institute and the global movement Brightline.

Footnotes:

1 Innovative application of project management methodologies on Sochi 2014, Russia’s first ever Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, PwC Case Study.

2 https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/megaprojects-the-good-the-bad-and-the-better

3 56 https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/do-you-need-business-ecosystem.aspx