The sea star syndrome: on the strategic choices of ecosystem participation

Geoff Tuff & Steven Goldbach

As two career consultants, it’s safe to say that we tend to get grouped with folk accused of promulgating buzzwords. So, we may be playing against type as we try to prevent another word from slipping into the realm of the meta-cliché. One of the great ironies in business is that we frequently take normal words and burden them with ever-deeper meaning, rendering them meaningless instead. In the recent past we smoothed away the edges of words like “innovation” and “digital” such that they more frequently elicit smirks than clarity or understanding. We appear to be dead set on doing the same to “ecosystems.”

Admittedly, not everything has to have a singular, shared, sharp definition to be valuable. Perhaps ecosystems can be treated as a broad-based concept that is applied uniquely within different organizations. But if that’s going to be the case, leaders can’t allow slop into their specific conception of what an ecosystem is or isn’t. If they do, it will increasingly lead to murky strategy choices. When sweeping generalizations like “we’ll win by being part of a technology ecosystem(!)” are substituted for genuine strategic choices, things eventually go badly.

Most of us first hear the word in primary school science class. According to a revered authority on the natural world – National Geographic – an ecosystem is “a geographic area where plants, animals, and other organisms, as well as weather and landscape, work together to form a bubble of life … Every factor in an ecosystem depends on every other factor, either directly or indirectly.” James Moore is widely credited with expanding the concept to the business world in a 1993 Harvard Business Review piece in which he wrote: “In a business ecosystem, companies coevolve capabilities around a new innovation: they work cooperatively and competitively to support new products, satisfy customer needs, and eventually incorporate the next round of innovations.”

Moore focused on innovation as the core objective within his initial definition of an ecosystem, but conceptually you can apply the notion of coevolving capabilities towards any business objective. When considered as a choice on the Strategy Choice Cascade, (first developed by our mentor and friend Roger Martin when he was a partner of ours at Monitor Group), participating in ecosystems can mostly be categorized as a way to build capabilities in support of your organization’s “Where to Play” and “How to Win” choices. That is the critical difference between ecosystems used for business and natural ones. Sea stars don’t get to pick which pool they will coexist in with others when the tide recedes. Businesses get to choose how and with whom they participate (or not) in ecosystems. This existence of choice means we are in the domain of strategy; unless you have explicitly declared the shape and make-up of the ecosystems you will play in (and those that you will not), then you don’t have a strategy. Yet many executives seem to act as if statements like “we will play as part of an ecosystem” are enough. As Roger taught us: if the opposite of your “choice” is simply a ridiculous statement, then you don’t have a strategy; you’re in the realm of business platitude.

You are already part of an ecosystem

Try as we might, we can’t think of a business that could credibly say it doesn’t participate in any ecosystem as part of its business model. Any company with a value chain – even if the outsiders comprise just suppliers, customers, and competitors – is technically part of an ecosystem. But even though they have existed forever in business history, ecosystems suddenly seem to be the hot new thing in management thinking. Creating porous organizational boundaries to access outside talent that might create some strategic advantage is not a new idea. “Joy’s Law” – the, perhaps apocryphal, observation by Sun Microsystems’ Bill Joy that, “no matter who you are, most of the smartest people work for someone else,” – has been kicking around for over two decades.

What is new is the urgency to access the best possible capabilities as quickly as possible just to survive, let alone be competitive. Digital giants are working hard to discover ways to leverage their platforms to expand into traditionally well-insulated industries. Smaller upstarts are using technology-driven business models to quickly unseat longstanding incumbents; think how quickly people are substituting in-home connected exercise equipment (e.g., Peloton) for gym memberships, a gradual trend that dramatically accelerated due to COVID-19. Increasingly, if an organization wants to remain competitive, it can’t rely on the capabilities it can conceivably create within its four walls. Further, because of technology, it’s becoming easier and easier to access the capabilities of outside organizations. So perhaps it’s no surprise that the topic of ecosystems is rising quickly on the strategy agendas.

Ecosystems are not new, but in the face of this new optionality, it is newly important that leaders need to make very clear ecosystem choices. Specifically, we believe leaders need to wrestle with two broad choices in particular:

- Where to Play (in ecosystems): For which business objectives should we leverage ecosystem partners (versus developing all the necessary capabilities ourselves) and therefore which other organizations should we work with towards our objectives?

- How to Win (in ecosystems): What form should our ecosystem take and how can we ensure that it results in our fair share of competitive advantage? How will we differentiate our ecosystem from others attempting to pursue the same objectives?

Where to Play: For what should we use ecosystems and who should be involved?

The most foundational choice that organizations need to make as it relates to ecosystems is what to use them for. While on the surface one could label this a simple choice, it isn’t in the least. There are several factors that need to be considered when evaluating whether to do something solely in-house or with one or multiple outside parties. They include:

- How much better (or cheaper) could we deliver against the business objective by working with outside parties?

- How quickly can we build the capability with others versus doing it ourselves?

- If we build the capability with others can our competition access similar (or even the same partners) to build the same capability?

Ultimately, each choice needs to be examined on its own merit and sadly, there is not a simple formula. One rule of thumb that we turn to is: if the capability is a critical part of delivering your organization’s overall differentiation, then it’s more important that that capability be proprietary in nature. If you can’t build the capability internally then you need to at least take steps to ensure the ecosystem you involve is somehow proprietary to your organization. If neither are true, your organization probably can’t be different.

If, on the other hand, the capability is not critically important to your overall differentiation, you should look for the most cost-effective way of delivering the required quality of the capability. This might mean outsourcing, building through an ecosystem, or building it yourself. But it’s not important to be proprietary if it’s not a component of your differentiation. It’s more important to be cost-effective.

If the “how to build it” resolves as a choice to build an ecosystem, then the question becomes “with whom?” If it needs to be proprietary, you need to seek out partners who are not your competition and will agree to play in this way. For instance, when Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JP Morgan sought a better healthcare solution, they formed an ecosystem to pursue it; healthcare was a critical component of their talent strategy, so they did not include competitive organizations initially. If the capability does not need to be proprietary, it might be advantageous to include your competition in the venture – such “co-opetition” shows up all the time in the automotive, technology, and pharmaceutical industries.

How to Win: How can our ecosystem be configured for advantage?

As the concept of business ecosystems ages, their types and specificity of purpose have blossomed. What used to be blurrily conceived of as some form of working collaboratively with others now has a range of increasingly specific nomenclature and business models. A transaction ecosystem like eBay is fundamentally different from an API ecosystem that enables the seamless service of Uber, even though both are focused on matching supply with demand. Supply chains are “the OG” ecosystems. Platforms have existed in tech for decades and they are now one of the de rigueur promises of would-be unicorns seeking funding. Multi-entity partnerships have long supported complex assembly processes such as automotive or aerospace manufacturing. And the more natural definition of self-sufficient interrelationships with built-in redundancy have helped collaborative efforts such as Mozilla or Wikipedia operate at massive scales. The trick for executives these days is to consider the ecosystem options in front of them in a way that allows them to make a choice that leads to advantage from participation.

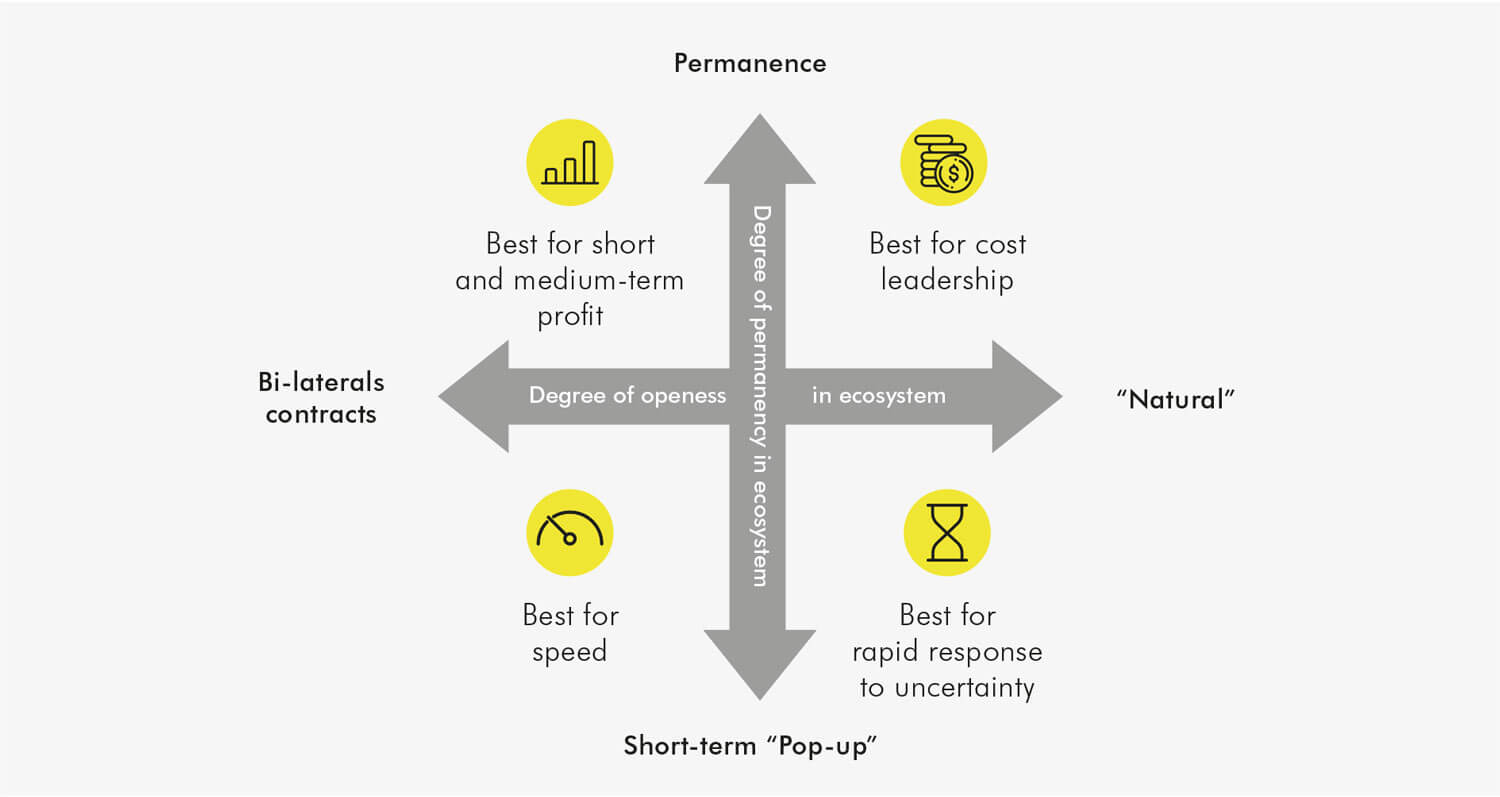

We use two dimensions to frame the options and, ultimately, the choice. The first dimension is around the degree to which the ecosystem is proprietary or open. The extreme end of the proprietary spectrum is the bilateral contract, and as you add parties but keep the system closed, you get the multi-nodal partnership, where there are a small number of players in the ecosystem, each uniquely contributing a specific capability that is unduplicated by the others. At the “open” extreme of the spectrum is what looks more like the “natural” ecosystem from science class. In it, there is likely to be a large number of varied participants, all working together as a system in which the whole is supported, as is each of the individual players. Importantly, there is room for capability overlap amongst the players and therefore some systemic redundancy. While participants have varying objectives, no one entity is so critical that the system fails if that entity dies or decides to leave.

The second dimension is the degree to which the ecosystem is intended to be short-term or permanent. Generally, most business structures of the past have relied on the presumption (or illusion) of permanence. With the accelerating rate of change in business models everywhere, however, that is no longer a given. In the very recent past we have seen something new: the emergence of “pop-up ecosystems.” As we struggled to contain and then respond to the dual health and economic emergencies of COVID-19, we saw largely self-organizing partnerships form for short-term needs. Erstwhile savage competitors in technology and retail worked together towards a common purpose. Traditional supply chain barriers were broken down in favour of achieving systemic efficiency. Most of these were ecosystems of convenience. No one expected these collaborations to exist forever, but for a period of time a number of businesses acted as if it was the new norm.

Bilateral and multi-nodal partnerships have long been an effective way for a small set of companies to come together with the primary purpose of maximizing profit. Typically, profits end up being distributed in rough correlation with the scarcity of the capabilities that are contributed, with the more important or more scarce contribution earning the higher profit. They benefit from being reasonably easy to set up as long as, a) a clear and shared objective exists, and, b) strict contracts and operating agreements prevent players from infringing on others’ turf. Because these ecosystems are contractual by nature, they require higher coordination and administrative costs, but for many players that may be worth the clear line-of-sight they have to making money in the short term. In the past, long-term deals between participants, each with durable individual competitive advantage, allowed this model to continue undisturbed. But because these are relatively “closed” ecosystems, with accelerating change the advantage they create has a decreasing shelf life. That is either because competition can, increasingly, quickly emerge from other consortia that have similar shared objectives (for example, the SkyTeam Alliance vs. the OneTeam alliance vs. the Star Alliance in the airline world) or because the rules and regulations needed to manage the partnership are not nimble enough to absorb changes in the business landscape.

Natural ecosystems, with many participants of each kind, tend to be more resilient than multi-nodal partnerships. These are self-organizing with no “loudest voice” and with some built-in overlap in roles. In these types of ecosystems, the redundancy means that no one can count definitively on their “fair share” but the long- term viability of the entity is higher: when one part of the system fails, the backups kick in. It’s harder for any individual player to make short-to-medium term profit in a natural ecosystem because their unique contribution is lower. But in the face of increasing uncertainty, many companies are willing to hand over some short-term gains in hope that they thrive for longer – the multiplayer ecosystem that is defined as “Hollywood” (think studios, talent agencies, production lots, writers, directors, actors, etc.) is a prime example of that.

As we consider this model and the examples above, it does make us wonder whether we are seeing a natural migration from the “top left” to the “bottom right.” We certainly see a migration from left to right on the chart, largely driven by COVID-19. Organizations will value the redundancy and resilience inherent in natural ecosystems that have multiple players of the same type. We may even see a migration from permanent structures to more semi-permanent structures as problems in business evolve at a faster rate. We think the shift from left to right is more certain than the shift from top to bottom. We would love to hear what others’ view on this shift might be.

Ecosystem participation is one of the few genuinely recursive strategic choices, requiring not just close attention but near-continuous monitoring and revisiting. Every time you make a shift in both your Where to Play and How to Win choices as relates to ecosystems, there will be a ripple effect through every other aspect of your strategy. And we are increasingly finding that no company should rest on its business model laurels in the face of uncertainty. Many learned this the hard way during the COVID-19 pandemic: who could have imagined that so many entrenched ways of doing business could be so fundamentally undermined in a mere matter of weeks?

As with any trend in management science, there will be leaders and laggards when it comes to exerting choice around ecosystem strategy. And the winners will almost surely be those who take a proactive stance, avoiding the fate of the wave-whipped sea star pulled by the nature’s forces from one tidal pool to another, never in control of its destiny.

Steven Goldbach is a Principal at Deloitte and serves as the firm’s Chief Strategy Officer. Prior to joining Deloitte, he was Director of Strategy at Forbes and a partner at Monitor Group.

Geoff Tuff is a principal of Deloitte Consulting and a senior leader of the Innovation and Applied Design practices. With more than 25 years of experience, Geoff’s work centers around helping clients transform their businesses to grow and compete in nontraditional ways.

They are authors of Detonate: Why – and How – Corporations need to Blow up Best Practices (and Bring a Beginner’s Mind) to Survive (Wiley, 2018).