Planting banyan trees: strategic leadership in the age of ecosystems

Jeffrey Kuhn

It has been a decade since Stephen Elop, Nokia’s then-CEO, published his Burning Platform memo on the company’s internal employee website. Since then, ecosystems — and whether to build, buy, or join one — have become a hot topic in boardrooms around the world.

In his communiqué, Elop lamented the calamitous decline of Nokia’s vaunted handset business after it was trounced by a one-two punch from Apple and Google. He acknowledged that the game had changed and questioned whether Nokia was fighting the right battle (let alone using the right weapons), writing: ‘The battle of devices has now become a war of ecosystems . . . our competitors aren’t taking our market share with devices; they are taking our market share with an entire ecosystem.’ Unfortunately, Elop’s wake-up call was too little, too late; competing ecosystems launched by Apple and Google had already eclipsed Nokia’s handset empire, essentially elbowing it out of its own business.

The stunning decline of Nokia’s handset business (at its peak, Nokia had nearly a 50 percent share of the global handset market) offers a cautionary tale to leaders of storied firms who have spent decades shoring up their supply chains and building impenetrable moats around their businesses only to have their markets co-opted by digital interlopers that apply ecosystem logic to siphon swaths of customers seemingly overnight. As Nokia painfully discovered, ecosystems do not observe traditional industry boundaries, nor play by the conventional rules of strategy. Given their protean nature, incumbent firms are unsure what they are competing against, let alone how to compete.

Paradigms lost: from walled fortresses to open ecosystems

For much of the twentieth century (and even today in many capital-intensive industries), established enterprises have operated with a ‘closed’ Chandlerian construct — a pervasive managerial belief system promulgated by its namesake Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., a business historian at Harvard Business School whose influential writings shaped the contours of industrial capitalism. In Chandler’s industrial paradigm, clear lines of demarcation delineate producers from consumers and value creation from consumption. Value is presumed to be created inside the enterprise with resources owned by the enterprise and then pushed out to the market for consumption. Aggregation of the factors of production is paramount in achieving organizational mass and economies of scale; byzantine hierarchies and mechanistic managerial systems are central to reducing variance, optimizing physical assets, and achieving a cost advantage.

Successful firms are said to run like well-oiled machines. Competition is a clash of titans — a game of organizational heft and clever chessboard maneuvering to achieve structural advantage and outwits rivals.

The Chandlerian construct suited the pre-digital age because the future looked a great deal like the past. Industries were composed of a handful of companies competing in structured markets that evolved linearly, with few strategic surprises. Incrementalism would suffice. Of course, those days have long since passed, and many of Chandler’s precepts have outlived their usefulness. Low-cost digital technologies have lowered barriers to entry precipitously, giving rise to new types of competitors and new ways of organizing economic activity and creating customer value.

Facing digital disruption, many old-line firms have undergone a religious conversion of sorts and have deployed a spectrum of ‘open’ organizational strategies and structures: multisided platforms, user- innovation communities, and ecosystems to (co)create customer and economic value using resources

outside the enterprise. For example, in 2014, agricultural equipment manufacturer Deere & Company (John Deere) launched MyJohnDeere.com, an ecosystem for agricultural producers that integrates a network of smart farm equipment, in-field sensors, and third-party software applications that provide weather, equipment performance, soil and irrigation, and crop data to farmers through a personal computer or mobile device. Danish toy company LEGO is another example. In 2020 it launched LEGO® World Builder, a crowdsourcing platform that brings fans and creator communities together to develop original stories in collaboration with LEGO’s creative team. And in a broadside against Amazon, Walmart joined forces with e-commerce platform Shopify to provide its legions of sellers access to the Walmart.com retail platform. In the digital economy, fluid business configurations such as these are commonplace.

Firms deploy business ecosystems for a variety of reasons, from building a defensive perimeter to shield against ecosystem envelopment (think Nokia) to enhancing its customer value proposition (think MyJohnDeere.com) to capturing recurring revenues from ecosystem partners (think Apple’s App Store). Ecosystems can take many forms but are generally defined as a confederation of organizations that collectively deliver coherent, integrated products, services, and experiences to customers, often through a digital platform. Business ecosystems are typically hosted by a central player with an established, market- leading brand who serves as the curator and orchestrator of the offerings provided by the ecosystem’s partners. As illustrated in the Haier example that follows, the host plays a keystone role in establishing cooperative principles and revenue-sharing agreements among ecosystem partners and in providing an identifiable brand and coherent end-user experience.

Planting banyan trees at haier

The movement is natural, arising spontaneously.

— I Ching

The Haier Group offers a vanguard example of the inner workings of an emergent, ecosystem-based business and the generative role that open organizational structures play in (co)creating customer and economic value and infusing new thinking and capabilities into the enterprise.

Established in 1984, Haier is a leading provider of large and small household appliances and consumer electronics, serving customers in more than 160 countries. Over the past four decades, the firm has undergone a remarkable metamorphosis, from a mainstream white goods manufacturer to its current incarnation as an ecosystem-based enterprise encompassing a labyrinth of interconnected businesses, from smart cities to education to health care. The firm’s unique, propagation-based growth model has germinated an autopoietic ecology of microenterprises that provide a steady stream of ‘edge’ businesses — bold, new-to-the-world ventures at the periphery of the core that pull the enterprise into the future.

As an open enterprise, Haier invites scholars from around the world to study its pioneering microenterprise model. In 2019, I had the honor of visiting Haier’s global headquarters in Qingdao, a picturesque coastal city in northeast China, to observe operations; interview a cross-section of microenterprise teams; and engage in strategic dialogue with executive leaders, including Haier CEO Zhang Ruimin.

I had followed Haier over the years through business journals and was familiar with its unconventional organizational model. Rather than till familiar soil and examine the nuts and bolts of its microenterprise model, I opted to break new ground and research the firm from a strategic, enterprise-level perspective. To prepare for my pilgrimage, I read several books and a stack of case studies and articles on the firm and eventually arrived at a conceptually oriented question that would provide a wide berth for my research: How does one lead an emergent, ecosystem-based enterprise strategically (compared to a conventional, hierarchical organization), and how does this recast the role of senior leadership?

At first glance, Haier’s hydra-like structure and intricate value creation and capture mechanisms can be difficult to decipher, even for seasoned strategists. My initial trip to Qingdao was admittedly one of those jump-into-the-rabbit-hole, paradigm-pummeling experiences, and I struggled to find my strategic True North: a recognizable core business to anchor my thinking. Upon returning home, I went into monk model — researching, reflecting, and writing — for several months until the implicit logic of Haier’s sophisticated strategy and business system eventually revealed itself.

Unknowingly, the seeds of my synthesis had been sown during the first few minutes of my visit to Haier, when during a tour of the firm’s executive building, my host paused in front of a live banyan tree planted in the lobby and described how the tree’s aerial root system sprouts new roots and trunks when its downward- growing branches touch the ground, expanding the tree’s footprint. (To put this into perspective, the Great Banyan tree in Kolkata, India, is believed to be 250-years old with more than 4,000 root-cum-trunk structures that collectively create a 156,000-square-foot-canopy.) Standing there in awe with my host, I appreciated the cultural significance of the majestic banyan tree as a symbol of immortality, but failed to grasp its strategic significance until several months later, when I realized that the banyan tree was a metaphor for Haier’s propagation-based growth model: a talisman of its regenerative capacity. The answer to my research question had unknowingly been right in front of me, hidden in plain sight, but I lacked the conceptual lens to perceive it: strategic leaders plant banyan trees.

Adapting haier to the digital age

Since the dawn of the internet, Mr. Zhang had been keenly aware that industrial society was approaching a turning point and transitioning to a new digital economy in which the vertically integrated empires of the industrial era stood little chance against the horizontal ecosystems of the digital age in satisfying customers’ personalized needs. In a world of ‘zero distance’ enabled by the internet, he was convinced that Haier would cede its market leadership if it did not master the logic of the digital economy and transform into a fluid, entrepreneurial enterprise embodying the connectivity and dynamism of this new era.

Building on earlier efforts to imbue a market mindset and shift the organization’s center of gravity closer to the customer, in 2005, Haier introduced the RDHY model which created a dynamic network of employee-run microenterprises. RDHY loosely translates to ‘employees and users become one’. Ren refers to employees, dan to user value, and heyi to connecting employees with users in a process of co-creation. In this new model, microenterprises operate autonomously and its team members are self- employed, self-organized, and self-motivated. They set their own strategies, make decisions independently without first gaining approval from higher-ups, elect their own leaders, hire (and fire) team members, procure services from internal or external providers, and determine their own compensation plans in accordance with agreed-upon performance targets. Harnessing the laws of natural selection, market- facing microenterprises are required to secure external funding — an important market signal — and invest personal funds in the venture, so that they have ample skin in the game. If a microenterprise cannot secure venture funding or advance orders through crowdfunding, Zhang suggested, then its business is not viable.

IoT ecosystems

The internet had introduced sweeping changes to the industrial order and Zhang was confident that the Internet of Things (IoT) would engender even greater changes that would create new customer needs and new sources of economic value. Haier originally conceived the RDHY model as a vehicle to create zero distance between its employees and users and to regain the entrepreneurial spirit of small firms. However, as the model matured, Zhang noted a powerful synergy between Haier’s mushrooming network of microenterprises and the IoT era, whose shape was beginning to take form. In this new era, he concluded, competition would be between ecosystems and ecosystem brands for life-long users, and value would be created with Haier-orchestrated ecosystems.

Since its introduction, the RDHY model has undergone several incarnations, commensurate with technological shifts in the external market landscape. In 2019, Haier introduced RDHY ‘3.0’ to support its IoT strategy by recasting its platform structure into a constellation of interconnected ecosystem-based businesses that provide users with integrated IoT-based offerings. Haier’s Smart Home Customization Ecosystem, for example, includes its Internet of Clothing, Internet of Kitchen, and Internet of Entertainment businesses. As Haier’s ecosystems take root, its products become mediums through which users can co-create unique personalized experiences through a community of ecosystem partners, generating recurring ecosystem revenues and a cycle of increasing returns for both Haier and its ecosystem partners.

A signature example is Haier’s Link Cook Series smart refrigerator which features a 21.5 inch high- definition touch screen that includes a calendar, a grocery list, menu selections, video and music streaming apps, social media and email access, and video and voice chat functions provisioned by ecosystem partners. Using IoT technology, the refrigerator can scan its contents and automatically replenish groceries through ecosystem partners, provisioned by Haier’s Internet of Food ecosystem. Like an iPad, users can configure personalized experiences with a host of software applications and ecosystem partners that are bundled into the appliance’s home screen. Haier’s smart refrigerator offers a window into a customer- centered future in which users can access a wide array of personalized offerings and experiences through a single gateway — in this case, a refrigerator — without leaving the ecosystem.

Strategic leadership in the age of ecosystems

Ecosystems play an important strategic role in creating and capturing value in conjunction with ecosystem partners and in safeguarding businesses from digital encroachment. The agricultural ecosystem orchestrated by John Deere, for instance, provides Deere a direct, curated relationship with its customers, and protects its flanks from incursions from AgriTech start-ups seeking a foothold with farmers: Deere’s customers. Empires and moats still exist in the world of ecosystems, but they take on a different, digital form.

Consistent with Chandler’s industrial economy, size still matters because the ecosystem’s value increases as more users and complementors participate, and the age-old stratagems of occupying the commanding heights, erecting barriers to entry, and protecting one’s flanks remain relevant.

To illustrate, I have outlined below the headlines from an analysis I conducted concerning the customer, competitive, and economic drivers of Haier’s ecosystem strategy:

- Maintain a direct, curated relationship with end customers to protect the firm’s flanks against direct competitors and digital interlopers.

- Create unique, durable points of differentiation to combat the relentless forces of of commoditization.

- Enhance the intrinsic value of offerings through comprehensive user interaction, ecosystem, and value co-creation mechanisms to counter the law of diminishing marginal utility.

- Grow an installed base of life-long users to capture recurring ecosystems revenues.

The parallels with classic competitive strategy are striking, but that is where the similarities end. There is a vast difference between leading an open, ecosystem-based enterprise optimized for emergence, and a closed, industrial-era colossus optimized for equilibrium.

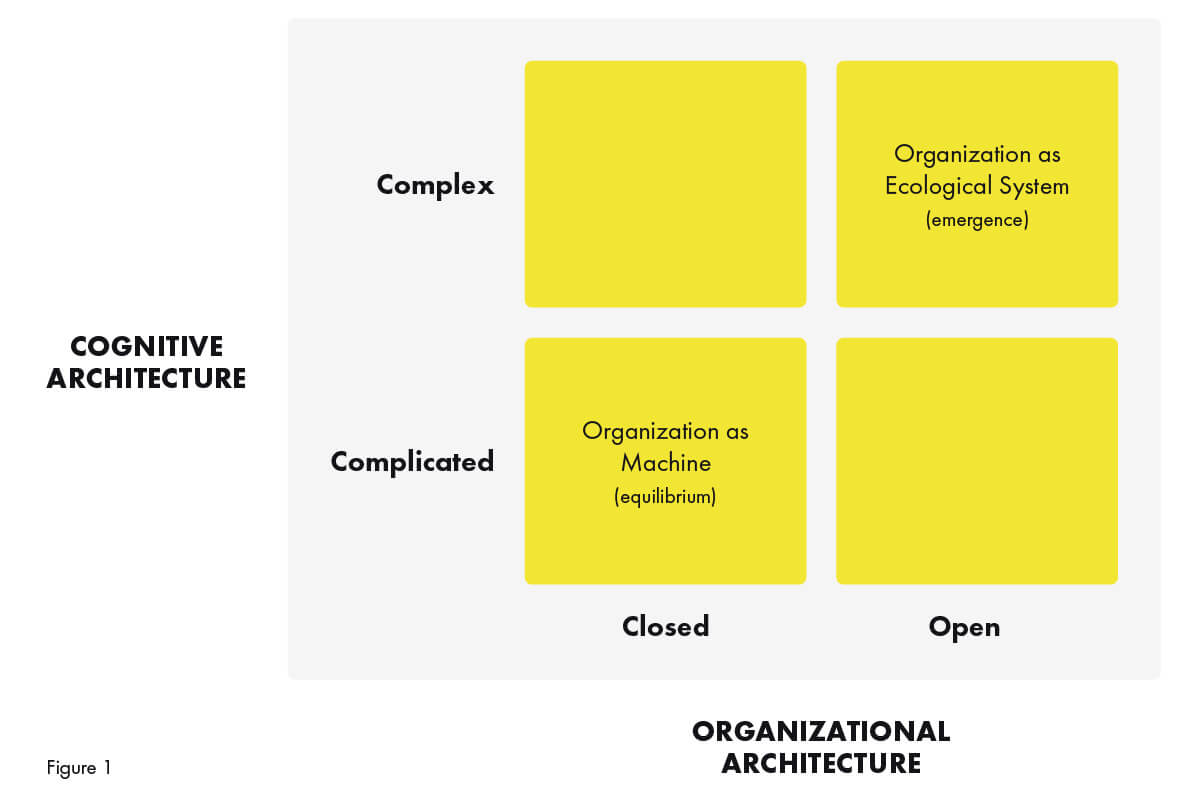

As the term implies, leading an ecosystem requires construing (in one’s mind) an organization as an ecological system, not as a machine — the dominant paradigm of the industrial era. As depicted in Figure 1, evolving one’s leadership worldview from a mechanistic (lower left quadrant) to an ecological systems perspective (upper right quadrant) requires two simultaneous transformations to catalyze the journey: from closed to open organizational architectures (horizontal axis) and from complicated to complex modes of thinking (vertical axis). An easy way to understand the latter is by comparing an Airbus A320 to a rainforest. An Airbus A320 is a complicated system. One can take it apart and put it back together piece by piece without changing its form. A rainforest a natural ecosystem is a complex system with dynamic properties that are in a constant state of flux. The slightest variation in any of its interdependent elements, such as a shift in weather patterns or the introduction of a new species, can affect the entire system in unforeseen ways. The same holds true for business ecosystems.

The mechanistic worldview of the industrial era — and its twin tenets of efficiency and control through ownership of the factors of production — has been etched into the minds of generations of denominator managers and continues to cast a long shadow over the way we think about and lead organizations. An ecosystem is not a machine. You cannot break it into discrete parts to understand how it works, and there are no levers to pull, gears to lubricate, or flywheels to spin — only seeds to plant (preferably banyan tree seeds), soil to nourish, and interactions to orchestrate. Darwin will take care of the rest.

When the student is ready, the teacher will appear

On my final day in Qingdao, I had the opportunity to meet with Mr. Zhang to share a synthesis of my interviews and engage him in conversation concerning the concept of leading with an ecological systems perspective and its association with autopoiesis, or organizational self-renewal. Most CEOs would sit there with a blank look on their face if I mentioned a term like autopoiesis, but Mr. Zhang is in a league of his own. To leaven the discussion, I shared that I had been seeking the Holy Grail of organizational renewal for more than two decades — a self-propagating, self-renewing enterprise — and had finally found it.

From there, we delved into the vital symbiotic relationship between personal renewal and organizational reinvention, drawing on Mr. Zhang’s leadership odyssey from hard-nosed field commander to ecosystem orchestrator as a point of comparison. In Haier’s early days, like many of his contemporaries, Zhang and his management team drew extensively on Chandler’s industrial-era playbook. However, as the competitive logic of the digital economy became clearer, he recognized the top-down leadership paradigms of the industrial era would be counterproductive in the bottom-up ecosystems of the digital age. In this new era, senior leaders were to be servants of the system, rather than bosses of employees, and he likened his role to that of a gardener who ‘creates favorable conditions and mechanisms for species in the Haier ecosystem to prosper in their own in a sustainable way’.

At the end of our conversation, Mr. Zhang expressed hope that the RDHY model would grow roots deep enough to withstand the relentless winds of organizational change, and as the enterprise matured into an autopoietic ecology of microenterprises, the question of who occupied the CEO chair would become less and less important.

As a researcher, life-changing conversations such as these are rare, and I gained a trove of insight concerning strategic leadership in the age of ecosystems through this experience. In the spirit of full disclosure, however, I must admit that my related quest to define Haier’s core business — and whether it even has one — remains a work in progress, but I have a hunch that it involves banyan trees.

Dr. Jeffrey Kuhn is an executive advisor and educator focused on enterprise strategy, leadership, and transformation. His work centers on helping senior business leaders develop the capacity to think and lead strategically in dynamic market environments undergoing profound change. He holds a doctorate from Columbia University and has served on the faculty of Columbia Business School.

Special thanks to the Haier Model Institute (HMI) and Columbia Business School for hosting my research.

Resources:

Nokia CEO Stephen Elop’s ‘Burning Platform’ Memo, Wall Street Journal, February 9, 2011, https://blogs.wsj.com/tech- europe/2011/02/09/full-text-nokia-ceo-stephen-elops-burning-platform-memo/.

‘Zhang Ruimin Discusses IoT and Life X.0,’ internal memorandum, Haier Group Cultural Industry Ecosystem.