A framework for regeneration: from community to country-as-a-platform

Christian Sarkar & Philip Kotler

In The Concept of the Corporation (1946), Peter Drucker warned us that the corporation is ‘in trouble because it is seen increasingly by more and more people as deeply at odds with basic needs and basic values of society and community’. Times change, but we still face the same predicament.

The digital revolution didn’t turn out as advertised. It brought us tech billionaires but didn’t increase the standard of living for the majority of people. Instead, income inequality grows and the digital divide persists. In the US, for example, a Pew survey reveals roughly a quarter of adults with household incomes below $30,000 a year (24 percent) say they don’t own a smartphone. About four-in-ten adults with lower incomes do not have home broadband services (43 percent) or a desktop or laptop computer (41 percent). And a majority of Americans with lower incomes are not tablet owners. By comparison, each of these technologies is nearly ubiquitous among adults in households earning $100,000 or more a year.

During COVID, inequality has risen to new heights, but even before the pandemic the world was in crisis. As humanity faces a growing number of existential challenges, we find that governments and institutions are not doing the job – they are failing us precisely at the moment we need them most. We’re facing an ecosystem of wicked problems.

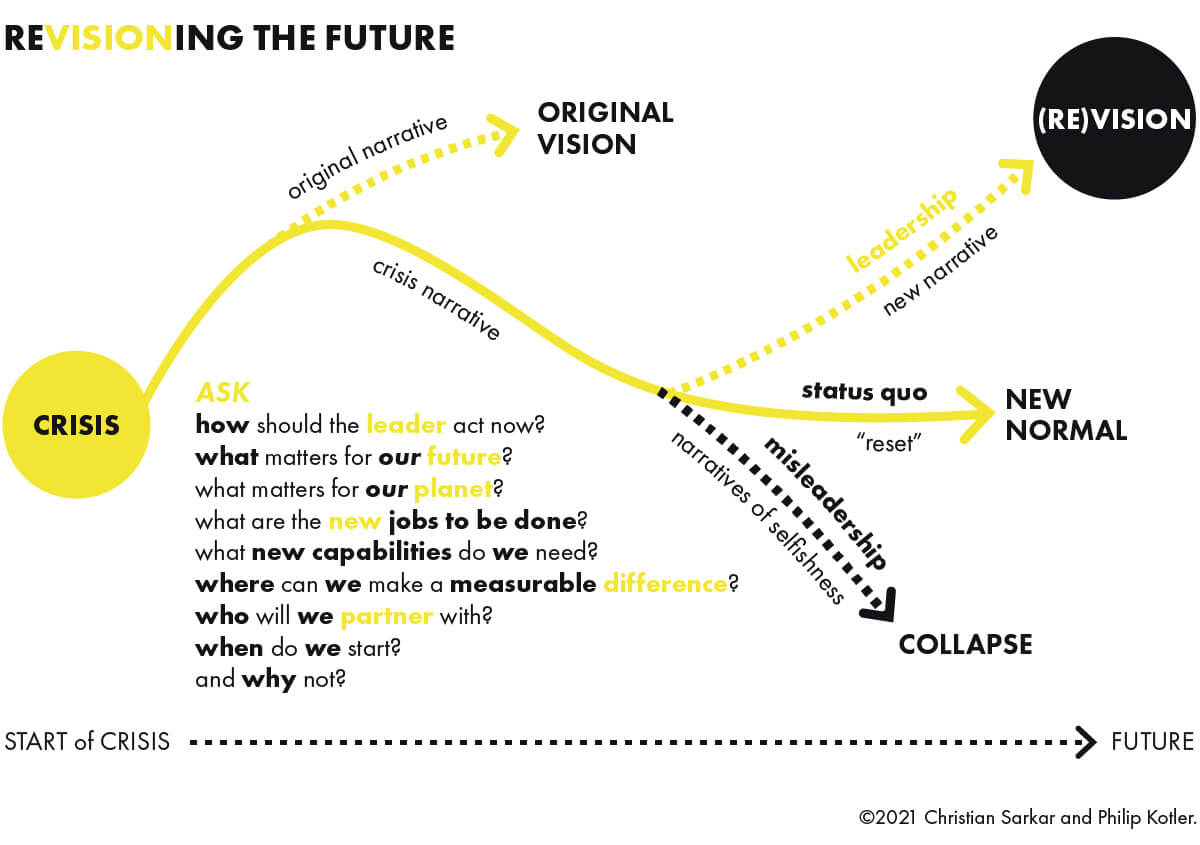

Revisioning the future

So, what can be done? What does ‘building back better’ actually mean? We cannot go back to a ‘new’ normal or the old one, because nothing about our current predicament is normal. We must re-vision: rethink what we want society to be. Do we want to continue destroying the planet or do we rally to save what’s left? And are our institutions capable of doing this?

The economic indicators we use are not just obsolete, but part of the problem, says UN Secretary- General Antonio Guterres:

Look at what’s happening with storms, with hurricanes, the rising sea level, glaciers melting, the ice- cap in the Arctic risking to disappear; with biodiversity being lost: one million species are at risk of disappearing. We see that the world we knew will change dramatically and will destroy life. And in the end it’s our life that will be destroyed. There is one thing that is a paradox: when you destroy a forest you are creating GDP – according to the statistics. When you overfish you are increasing your GDP – according to the statistics – when you destroy the planet … you are showing an increase of GDP so even that needs to be changed. We need to have a new way to measure our economy to measure our activity to make sure that we take into account the dramatic cost that we all face by the destruction of nature.

This statement from the leader of the most important global institution of our time begs us to think of a new approach. What theories and concepts can we bring together to do this? Our list includes the following:

- A Declaration of Interdependence

- The Principles of Design Justice

- Zero Distance to the Community

- Regenerative Marketing

- Hybrid Development Models

Taken together, these five principles are the foundations of a new approach for the future based on the well-being of its communities – we call it ‘Country as a Platform’.

The Declaration of Interdependence

What is needed now more than ever is a ‘declaration of interdependence’, according to Henry Mintzberg, who rightly worries that our world has reached the limits of growth driven by the pursuit of individual rights at the expense of shared responsibilities. He has proposed the following resolutions:

- Balance begins when each of us decides how we shall become part of the By doing nothing, we remain part of the problem.

- We advance to action in our communities, networked to consolidate a global movement for peaceful reformation.

- We commit to the ideals of social conscience, fair trade, and good government, to replace the dogma of imbalance—that greed is good, markets are sufficient, and governments are We explore our human resourcefulness by resisting our exploitation as human resources.

- We build worthy institutions in all three sectors of society—departments in government, enterprises in business, associations in communities—from the ground up, with widespread engagement that carries individual leadership into collective communityship.

- At the tables of public policy, we strive to replace the compromises of self-interest with the coalescing of common interest.

- We challenge the rampant corruption that is legal as vigorously as we expect our governments to prosecute the overt corruption that is criminal.

- Sustainable global balance requires substantial global government. We call on all democratic nations to rally for lasting peace, by containing any power that aims to dominate while holding economic globalization in its place, namely the marketplace.

Mintzberg tells us emphatically: ‘These resolutions require concerted action, not by centrally orchestrated planning so much as through a groundswell of initiatives by concerned citizens the world over, to restrain our worst tendencies while encouraging our best. For the future of our planet and our progeny, this is the time to get our collective act together.’

The principles of design justice

How do you design systems so that the outcomes of these systems are just? The Design Justice Network gives us a few pointers. Let’s begin by understanding what is meant by the term ‘designing for justice’:

Design justice rethinks design processes, centers people who are normally marginalized by design, and uses collaborative, creative practices to address the deepest challenges our communities face.

The principles of design justice are based on a new lens of value: design must consider the impact on the community and those impacted (including the planet). Our design thinking schools cannot easily embrace this view, because they are still centered on profit. Here are 10 guiding principles of design justice:

- We use design to sustain, heal, and empower our communities, as well as to seek liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems.

- We center the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcomes of the design process.

- We prioritize design’s impact on the community (and planet) over the intentions of the

- We view change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process, rather than as a point at the end of a process.

- We see the role of the designer as a facilitator rather than an expert.

- We believe that everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience, and that we all have unique and brilliant contributions to bring to a design process.

- We share design knowledge and tools with our communities.

- We work towards sustainable, community-led and -controlled outcomes.

- We work towards non-exploitative solutions that reconnect us to the earth and to each other.

- Before seeking new design solutions, we look for what is already working at the community We honor and uplift traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge and practices.

These principles are a starting point for any project of the future, and must be given far more visibility and consideration, not just in the world of design, but also the wider systems of our society – economic, social, political, environmental, etc.

Zero distance to the community

Post-COVID, what can be done to create value for society and communities? In business we view value-creation as a partnership – at best – between value created for the company and value created for customers. But, if we turn to our principles of design justice, we must also consider the following question: what value are we creating for the community and the planet?

In essence, we seek zero distance to the community. This is an idea that comes to us from Haier’s Zhang Ruimin who has created a company radically organized around the customer, best captured by his phrase: ‘create zero distance with the customer’.

How do we do this?

Those of us who have been building digital communities know that we are simply trying to re-interpret and re-create the rules of real, living, communities. The activist and author Wendell Berry had something say about this many years ago which applies to the ecosystem builders of today. Here are some of his key points:

Supposing that the members of a local community wanted their community to cohere, to flourish, and to last, they would:

- Ask of any proposed change or innovation: What will this do to our community? How will this affect our common wealth?

- Include local nature — the land, the water, the air, the native creatures — within the membership of the community.

- Ask how local needs might be supplied from local sources, including the mutual help of

- Supply local needs first (and only then think of exporting their products, first to nearby cities, and then to others).

- Understand the ultimate unsoundness of the industrial doctrine of ‘labor saving’ if that implies poor work, unemployment, or any kind of pollution or contamination.

- Develop properly scaled value-adding industries for local products in order not to become merely a colony of the national or the global economy.

- Develop small-scale industries and businesses to support the local farm or forest economy.

- Strive to produce as much of their own energy as possible.

- Strive to increase earnings (in whatever form) within the community and decrease expenditures outside the community.

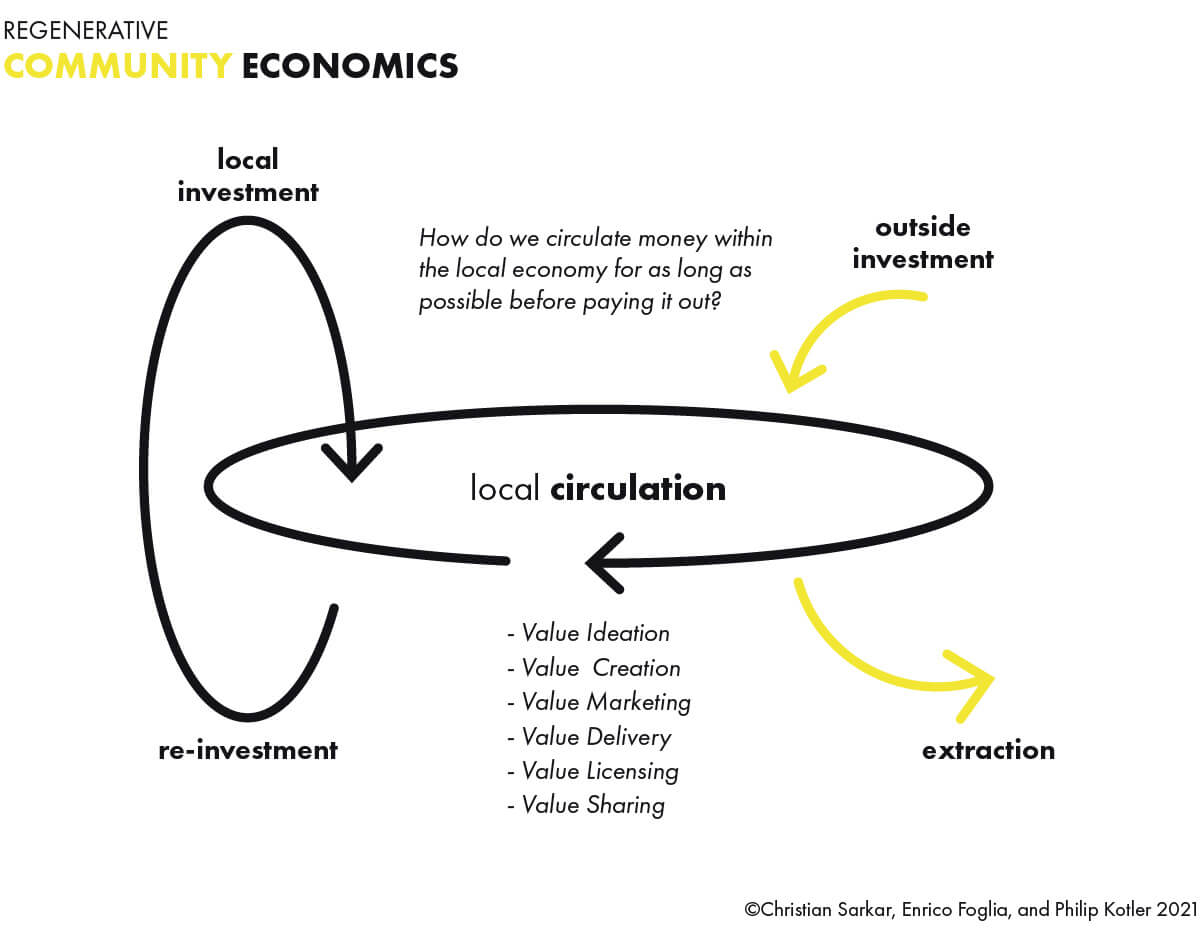

- Circulate money within the local economy for as long as possible before paying it out.

- Invest in the community to maintain its properties, keep it clean (without dirtying some other place), care for its old people, and teach its children.

- Arrange for the old and the young to take care of one another, eliminating institutionalized childcare and homes for the aged. The young must learn from the old, not necessarily and not always in school; the community knows and remembers itself by the association of old and young.

- Account for costs that are now conventionally hidden or ‘externalized.’ Whenever possible they must be debited against monetary income.

- Look into the possible uses of local currency, community-funded loan programs, systems of barter, and the like.

- Be aware of the economic value of neighborliness — as help, insurance, and so on. They must realize that in our time the costs of living are greatly increased by the loss of neighborhood, leaving people to face their calamities alone.

- Be acquainted with, and complexly connected with, community-minded people in nearby towns and cities.

- Cultivate urban consumers loyal to local products to build a sustainable rural economy, which will always be more cooperative than competitive.

Regenerative marketing

Now, in 2021, we are exploring these community-centric concepts as part of our research at The Regenerative Marketing Institute – an institution we co-founded with Enrico Foglia, the head of Kotler Impact, Europe. Regenerative marketing is defined as marketing practices which nurture communities and build local prosperity over the long term. The outcomes of regenerative marketing include value creation for customers, employees, and local communities.

Regenerative marketing practices must – by definition – build community wealth. Preliminary research findings from Italy suggest the following positive characteristics of businesses committed to regenerative marketing:

- The Founding Mission: the business has kept its founding spirit alive, often rejuvenated by the current leadership

- Leading with Trust: the company is built on trust-based architectures and business models

- Commitment to Community: the enterprise has deep local roots and is designed to improve community wellbeing

- Imagination-driven Innovation: the business builds unique, differentiated products

- Time-Equity: the institution invests in building customer and community intimacy and puts in the time to create deep connections

- Cultural Traditions: the company balances traditions and “family” values with competitive pressures

- Collaboration Platforms: the company builds a community-centric platform for creating community value

- Multi-generational Loyalty: employees and their families have a life-long relationship with the business, often over multiple generations

- Customer Focus: customer relationships are built on deep trust, not exploitation

- Local Funding: Financial support from local based banks and financial institutions tightly connected with the local community so that access to the credit is easier thanks to long term personal relationships.

- Local Circular Economy: supplier, partners, consultants are chosen among local community creating a common vision where the success of the company is shared with community stakeholders

- Local Sustainability: great attention to local environmental practices where most of the time the founders and his/her family reside

Why does regenerative marketing work? In our 2021 interview with Enrico Foglia he explained: ‘Regenerative marketing is about deep trust. It begins (and ends) with the relationships with the local community. In fact, the business may even be community-owned. This creates a new domain for value creation ignored by traditional business school thinking: community value creation.’

Community value creation is not without controversy. In The Careless Society: Community and Its Counterfeits, John McKnight warns: ‘More and more conditions of human beings are being converted into problems in order to provide jobs for people who are forced to derive their income by purporting to deliver a service.’

We ‘fix’ problems by making them worse. The diagnostic approach used by consulting firms is part of the problem. By creating a needs-driven list of deficiencies and problems, we turn citizens into consumers of social and service systems. They lose their sense of agency and become passive consumers of social services.

Elsewhere, McKnight explains:

It is important to recognize that the language we use to define the purpose of an association or meeting often puts people in a box that limits their productivity. The ‘problem’ box usually focuses on a negative aspect of community and a resolution provided by institutions. The asset-based approach is a box that usually focuses on creativity produced by citizens. One of the reasons we may have so little productive citizen creativity at the local level is that people buy into the belief that the purpose of getting together is to deal with a problem. There is another purpose that is probably more important and that is engagement that mobilizes citizen creativity and contributions. Perhaps we need a name for this. It is not problem solving. It is mobilization of creative vision.

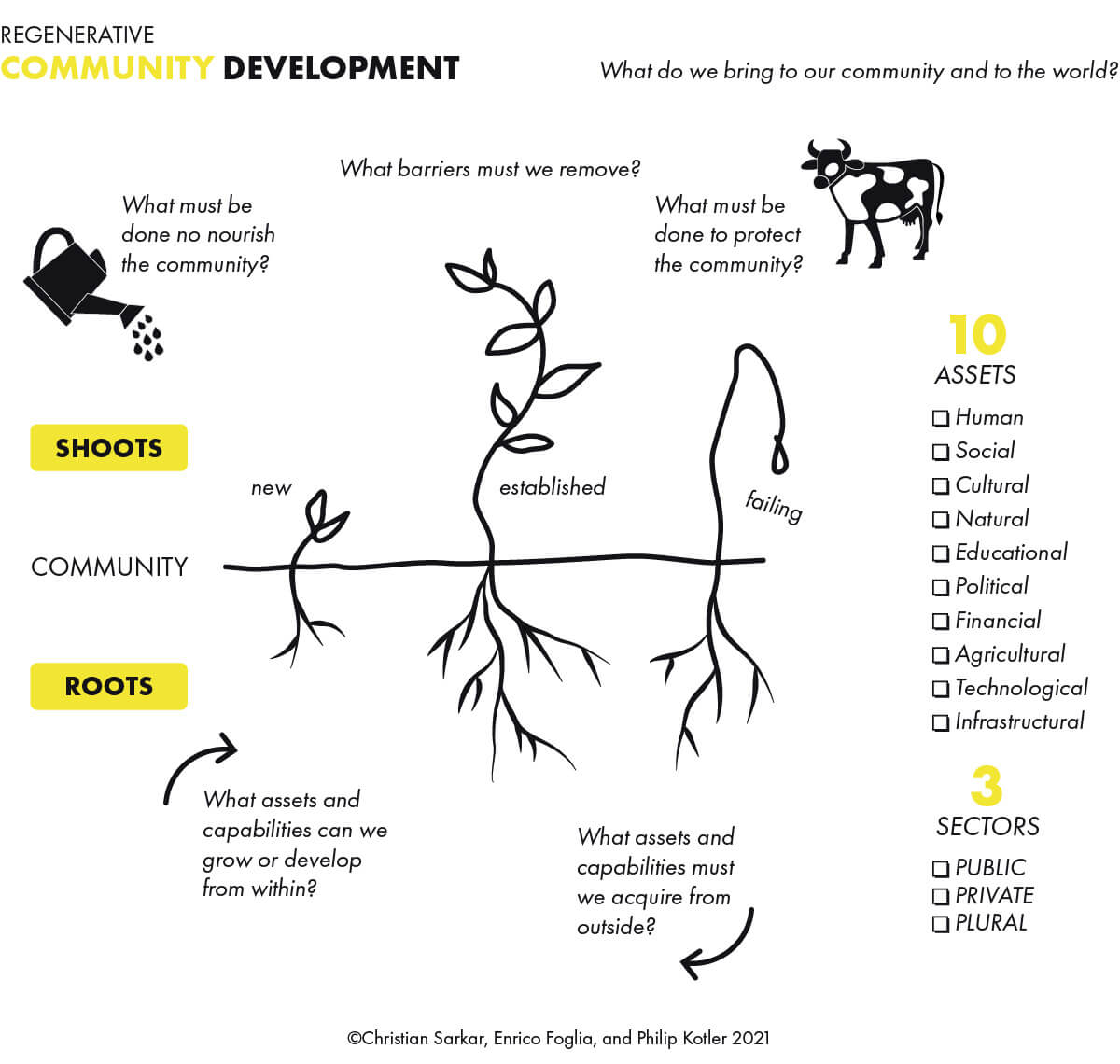

McKnight insists that the essence of community regeneration is when people who are defined as problems achieve the capability to address the problem. We begin by identifying the assets -- the strengths and capabilities -- already present in the community. It is the living relationships and connections between these assets which build and empower the citizens, associations, and enterprises which make up the community.

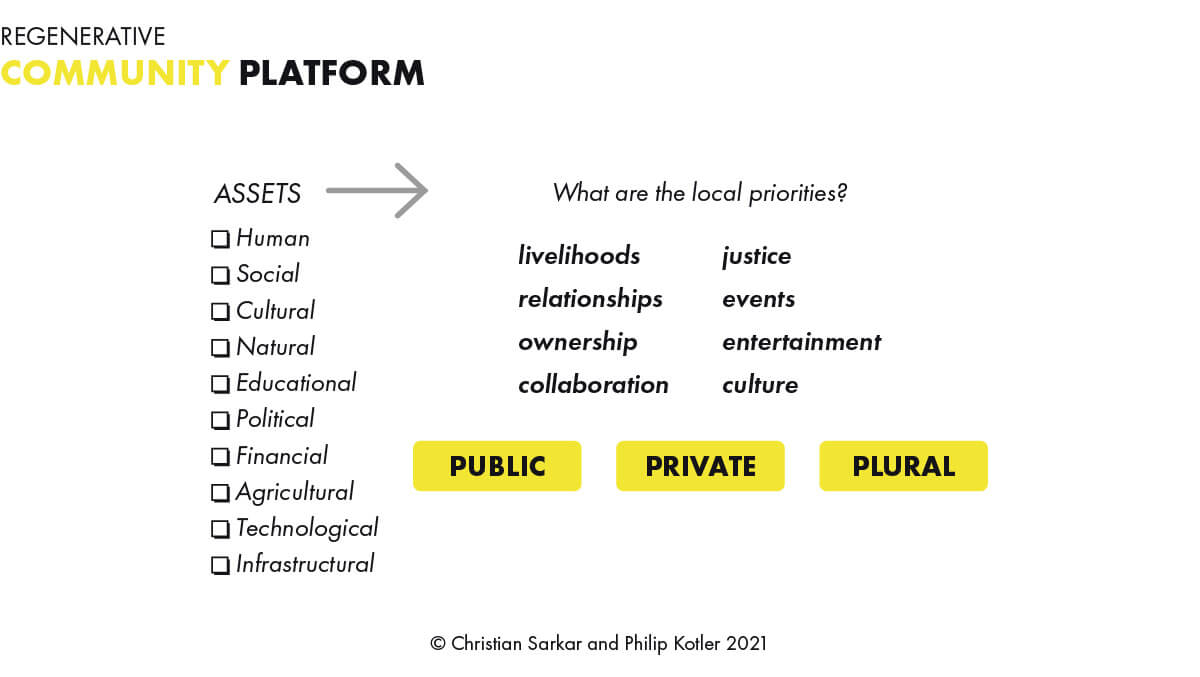

Thus, we have expanded on McKnight’s asset-based approach to identify 10 community-based assets:

- Human

- Social

- Cultural

- Natural

- Educational

- Political

- Financial

- Agricultural

- Technological

- Infrastructural

The primary stakeholder is the community – the individuals and associations of the local village or neighborhood.

Hybrid development models

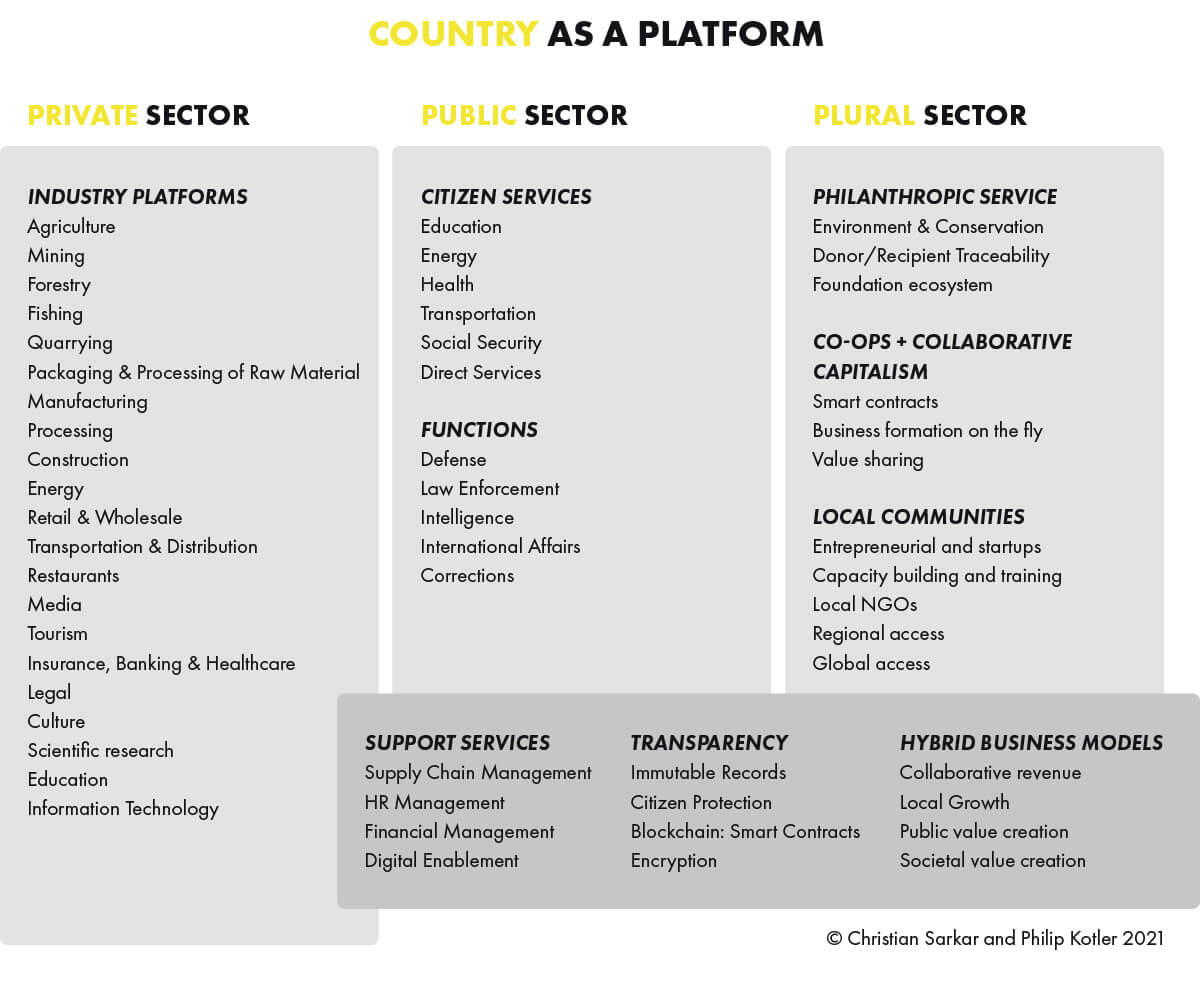

In his e-pamphlet — Rebalancing Society — Henry Mintzberg points out that a balanced society can be thought of as ‘sitting on a stool with three sturdy legs: a public sector of respected governments, to provide many of our protections (such as policing and regulating); a private sector of responsible businesses, to supply many of our goods and services; and a plural sector of robust communities, wherein we find many of our social affiliations’.

Unfortunately, many private-sector business leaders function under the myth that they alone create value, and the public and plural sectors simply get in the way. And, in the United States, for example, the private sector dominates society to such an extent that it is unlikely to be dislodged by political mandates.

Changing this power dynamic isn’t possible top-down. We’ve all heard about public-private partnerships, but why don’t we hear more about public-private-plural models?

In the developing world, one of the primary reasons for the failure of development projects is that they cannot be sustained. Traditional approaches don’t always work; as soon as the development institutions (NGOs, agencies) leave, things fall apart. Soon the project is either abandoned or simply turned off. This happens all the time with water and energy projects.

One way to work around this and make it stick is to involve women in the project. This has been the secret behind the success of organizations like Grameen and the Solar Electric Light Fund. When women lead and control their own destinies, stuff happens. This is a lesson learned in the field, but overall the development-through-empowering-women movement has struggled for years.

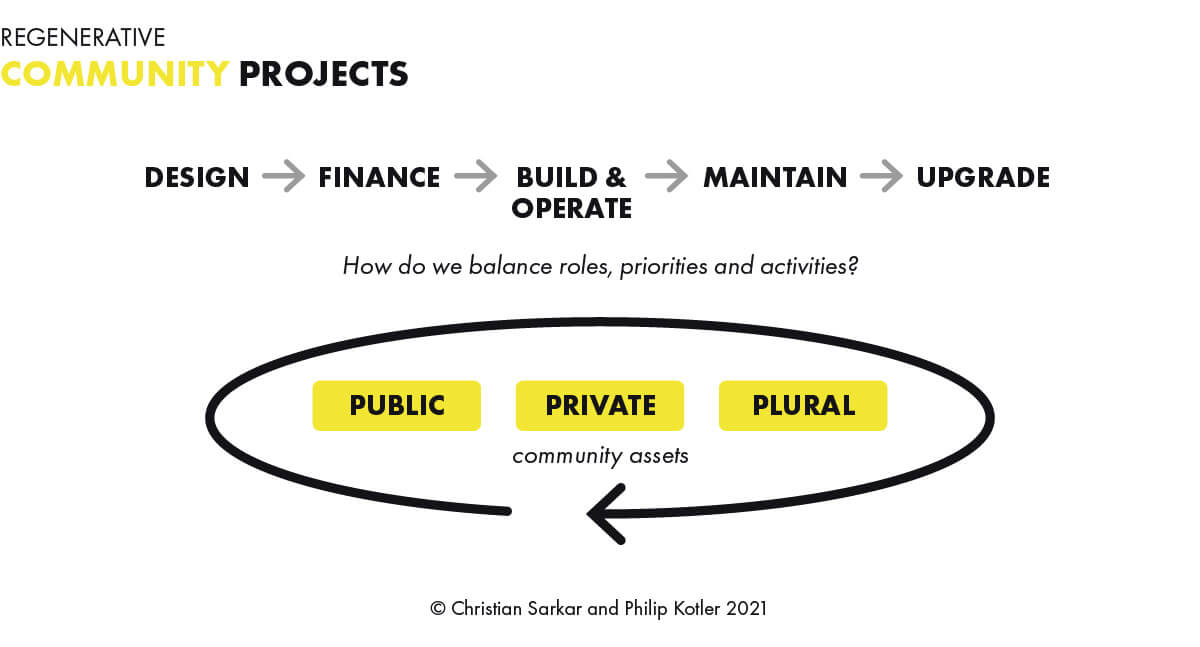

Let’s examine at how a hybrid or collaborative business model might be used to empower community residents and deliver needed services as a regenerative community project. Here are what the hybrid phases might look like:

Design: the community works with local community assets – civil authorities, NGOs and businesses – to envision a solution that works for the community.

Finance: the community pools its resources to fund the initiative with the help of matching government private investments.

Build & Operate: the community works with the private sector to build and operate the project. The government may subsidize or donate resources as well.

Maintain: may include jobs for the community and training services from a local NGO or association

Upgrade: all players come to the table to develop the next level of improvements.

Is it too much to ask governments, NGOs, development institutions, and businesses to work together with the impacted communities to build integrated solutions?

The key ingredient is trust and solidarity. For example, Partner In Health (PIH), one of the world’s most famous NGOs, believes it is essential to partner with the community. They hire and train local staff. They work with governments to reinforce national health services so more people receive services. They collaborate with other health workers such as traditional birth attendants and government health workers because together they can have a stronger impact. PIH has established a community-based model of care that is now viewed as a leading health-care delivery model in the developed world.

Businesses must learn to do the same. Inclusive growth can only be driven by inclusive business practices. And of course, they must be sustainable.

From community to country-as-a-platform

Too often we operate under the mistaken assumption that private or state digital platforms are the only solutions available for digital community enablement.

As top-down, country-based platforms continue to grow, Sangeet Paul Choudary points out that control over the trade in goods and services shifts from countries to digital platforms. He explains the ramifications:

Public and private actors in China are working in close cooperation—in a country-level platform strategy—to create digital infrastructure that aligns with the BRI, to promote standards that drive the adoption of such infrastructure, and to strengthen China’s points of control in the digital economy. This strategy extends across four key themes: trade, payments, smart cities, and social credit. If successful, this strategy could fundamentally shift trade and financial flows toward a China-centric economic order and could even reshape political systems in participating countries.

The weakness of this platform strategy is that it is grounded on the same fallacy that McKnight warned us about, it is a top-down, needs-based transaction system which fails to build local trust.

And that is an opportunity for community-based platforms. Local ownership or municipal ownership of community platforms allows for greater flexibility and local empowerment. The opportunity is a bottom-up platform which is built by communities, for communities.

The growing importance of the groups like the Platform Cooperativism Consortium are creating a space for community collaboration. Platform cooperatives are businesses that use a website, mobile app, or protocol to sell goods or services. They rely on democratic decision-making and shared ownership of the platform by workers and users. Their tool library is a place for co-ops to find and share digital tools with each other.

They are justifiably upset with ‘platform capitalism’ because they view the Internet slipping out of ordinary users’ control. Their point-of-view:

The power held by principal platform owners like Uber, Amazon, and Facebook has allowed them to reorganize life and work to their benefit and that of their shareholders. ‘Free’ services often come at the cost of our valuable personal information, with little recourse for users who value their privacy.

The paid work that people execute on digital platforms like Uber or Freelancer allows owners to challenge hard-won gains by 20th-century labor struggles: workers are reclassified as ‘independent contractors’ and thus denied rights such as minimum wage protections, unemployment benefits, and collective bargaining. Platform executives argue that they are merely technology (not labor) companies; that they are intermediaries who have no responsibility for the workers who use their sites. The plush pockets of venture capitalists behind ‘sharing economy’ apps allow them to lobby governments around the world to make room for their ‘innovative’ practices, despite well-substantiated adverse long-term effects on workers, users, the environment and communities. At the same time, in the gaps and hollows of the digital economy, a new model follows a significantly different ethical and financial logic.

Bottom line? The Internet can be owned and governed differently.

Given all of this is it any wonder that we are beginning to see a new wave of startups and businesses striving to do good, to create a platform around purpose? For example:

- Up & Go offers professional home services like house cleaning, (and soon childcare and dog walking) by those who are looking for assistance with laborers from local worker-owned cooperatives. Unlike extractive home-services platforms which take up to 30 percent of workers’ income, Up & Go charges only the 5 percent it needs to maintain the platform.

- Fairbnb.coop is a vacation rental platform which gives back 50 percent of its revenues to support local community projects of your choice such as social housing for residents, community gardens and more.

- MiData is a Swiss ‘health data cooperative’, creating a data-exchange which will securely host member-users’ medical MiData aims to out-compete private, for-profit data brokers and ultimately return the control and monetization of personal data to those who generate it.

- Gratipay provides a free subscription-based patronage infrastructure for developers of open- source ventures, by enabling credit-card transactions at-cost, subtracting only the processing fees from users’ subscriptions.

- MyCelia’s goal is to empower a fair, sustainable and vibrant music industry ecosystem involving all online music interaction They seek to unlock the huge potential for creators and their music related metadata so an entirely new commercial marketplace may flourish, while ensuring all involved are paid and acknowledged fully, and to see that commercial, ethical and technical standards are set to exponentially increase innovation for the music services of the future.

All of these businesses are developing ecosystems and platforms built around connecting customers with the job to be done, for less, or for free. They are seeking to build a more equitable, common platform for value exchanges. What happens when this bottom-up approach goes nationwide?

The result is what Istakapaza CEO Alok Sinha calls ‘Country as a Platform’ – a community-based approach that is being developed in India to include all sectors: public, private, and plural.

‘Our goal is start by building deep vertically-integrated platforms that empower not just the big industry players but small startups and local entrepreneurs in a seamless experience,’ explains Sinha. ‘The strategy is one of inclusivity and local empowerment in Tier 1, 2 and 3 cities across India. We say that no one owns the ecosystem, we are all participants.’

This is a step in the direction of citizen-owned public platforms. What if there was a non-profit version of Facebook? What if your local post-office was a public platform for banking, for e-commerce, for community digital enablement?

We are on the cusp of a new paradigm: a regenerative economy.

Philip Kotler is known as the ‘father of modern marketing’. For over 50 years he has taught at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. His book Marketing Management is the most widely used textbook in marketing around the world. He received his M.A. degree in economics (1953) from the University of Chicago and his Ph.D. degree in economics (1956) from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is author of over 150 articles and 80 books, including Principles of Marketing, Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, Strategic Marketing for Nonprofit Organizations, Social Marketing, Marketing Places, The Marketing of Nations, Confronting Capitalism, Democracy in Decline, and Advancing the Common Good.

Christian Sarkar is an author, entrepreneur, artist, and consultant He is founder of Double Loop Marketing, a marketing consultancy. He is also co-founder (with Philip Kotler) and editor of The Marketing Journal and founder of Ecosystematic, an ecosystem strategy consultancy. Christian is involved in numerous non-profit and public-education projects, including The Wicked7 Project, FIXCapitalism.com and the $300 House Project. In 2021 Christian was named to the Thinkers50 Radar of global management thinkers primarily for his work on brand activism.

Resources:

Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption, Emily A. Vogels, Pew Research Center (June 22, 2021); https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/22/digital-divide-persists-even-as-americans-with-lower-incomes-make- gains-in-tech-adoption/.

‘COVID-19 is increasing multiple kinds of inequality. Here’s what we can do about it’, World Economic Forum, Oct 9, 2020; https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/covid-19-is-increasing-multiple-kinds-of-inequality-here-s-what-we-can-do- about-it/.

Christian Sarkar, ‘The Ecosystem of Wicked Problems’, Global Peter Drucker Forum, (November 12, 2019); https://www. druckerforum.org/blog/the-ecosystem-of-wicked-problems-by-christian-sarkar/.

‘What It’s Like to Lead the UN in 2021’, YouTube video, March 31, 2021; https://youtu.be/p1nzi21m2Zc. Henry Mintzberg, ‘The Declaration of Our Interdependence’; https://ourinterdependence.org/.

The Design Justice Network https://designjustice.org.

Design Justice Network Principles, Summer 2018; https://designjustice.org/read-the-principles.

Bill Fischer, Umberto Lago, and Fang Liu, ‘The Haier Road to Growth’, strategy +business, April 27, 2015; https://www.strategy- business.com/article/00323.

Wendell Berry, speech delivered November 11, 1994 at the Northern Plains Resource Council; https://sustainabletraditions.com/2010/10/wendell-berry-17-rules-for-a-sustainable-local-community/.

The Regenerative Marketing Institute, 2021; https://regenmarketing.org.

Enrico Foglia, Christian Sarkar, and Philip Kotler, ‘Regenerative Marketing: Lessons Learned from Italian Business’, The Marketing Journal, June 16, 2021; https://www.marketingjournal.org/regenerative-marketing-lessons-learned-from-italian-business-enrico- foglia-christian-sarkar-and-philip-kotler/.

Sangeet Paul Choudary, ‘China’s country-as-platform strategy for global influence’, Brookings Institute, November 19, 2020; https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/chinas-country-as-platform-strategy-for-global-influence/. John McKnight, The Careless Society: Community and Its Counterfeits, Basic Books, 1996.

The Problem with Problems (Leaning One) John McKnight; https://johnmcknight.org/the-problem-with-problems-leaning-one/.

Christian Sarkar, ‘Ecosystem Development: Needs vs. Assets’, February 14 2013; https://christiansarkar.com/2013/02/ecosystem-development-needs-vs/.

Henry Mintzberg, Rebalancing Society, Berrett–Koehler, 2015; https://mintzberg.org/sites/default/files/page/rebalancing_full.pdf.

Christian Sarkar, ‘Hybrid Business Models: Impact Innovation and the Quest for Collaborative Profit’, October 3 2013; https:// christiansarkar.com/2013/10/hybrid-business-models-the-que/.

Andrea Cornwall, ‘Donor policies fail to bring real and sustained change for women’, The Guardian, March 2012; https://www. theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2012/mar/05/women-route-to-empowerment-not-mapped-out.

Platform Cooperativism Consortium https://platform.coop.

Interview with Alok Sinha, CEO, Istakapaza.com.