Building a butterfly brand

Peter Fisk

Mikkel Bjergso loves beer. So much so that the tattooed Dane, who was previously a physics teacher, has become the global leader of the craft beer market. “Forget all this technology,” he tells me while sitting in his Copenhagen bar, “in today’s world people want to have time to be human, to be individual, to discover simple pleasures in life.”

Bjergso used to choose the cheapest, blandest beer, until one day he tasted Hoegaarden beers from Belgium, which changed his life. In 2006 he started home brewing in his kitchen to create his first craft beer, while still teaching by day. His breakthrough came when he started to experiment with additional ingredients, adding French coffee to oatmeal stout, creating what he labelled “Beer Geek Breakfast.”

His Copenhagen-based business, Mikkeller, has launched a staggering 1680 types of beer over the last five years, and created its own branded bars in over 45 cities from San Francisco to Seoul, Tokyo to Torshavn, capital of the Faroe Islands.

Yet Bjergso never wanted to create a business, with all the costs of infrastructure, people, and production. Instead, the business is largely virtual, each of the beers is made by independent brewers around the world, and the bars are run by local partners. Mikkeler is essentially a platform business, albeit more physical than digital.

He became known as “the gypsy brewer,” travelling the world in search of the best craft beers, and then linking the local microbrewery to his growing network.

He sees Mikkeller as a lifestyle brand, creating a range of branded hoodies and beanies plus beer festivals and a running club. The Mikkeller Running Club is a big passion of Bjergso, with over 250 chapters around the world, and was voted the world’s best running community by Runner’s World magazine.

Bjergso, an enthusiastic runner himself, says: “The aim of the Mikkeller Running Club is simple: stay fit through running and drink loads of beers. On the first Saturday of every month, members of the various chapters gather to run together and then enjoy a free beer at a clubhouse bar. Some people are more serious about the running, others are more interested in the beer.”

Ecosystems from beer to beauty

Emily Weiss is intent on disrupting the $250 billion cosmetics industry, which is still dominated by traditional brand owners like L’Oreal and Estee Lauder. “Women today have different needs than we had in the past, but beauty companies haven’t responded to that,” she says.

Her journey started when she was a 25-year-old fashion assistant at Vogue and started writing her own blog in the evenings, “Into the Gloss.” She wanted to connect with real people like her, and rapidly built up a following by taking her followers into the bathroom cabinets of women she met, a popular feature of her blogs.

An early adopter of Instagram, she focused on photos that were rapidly shared by her community. Her blog soon became far more significant than Vogue to her audience. It became the must-read for beauty fans, with over 10 million page views a month, and she realized she needed to focus on it full time.

She launched Glossier in 2014 as a socially driven online cosmetics business that grew rapidly with the help of $2 million venture funding. She focused on creating content and cosmetics products for women like herself, “useful and affordable, for girls who work hard but want to have fun.”

Glossier became the cult beauty brand for the Instagram generation.

Products were cocreated – driven directly out of discussion forums, sales multiplied through peer-to-peer recommendations, and the brand spread rapidly through social media. The pink and white branding rapidly spread across a range of products from cleaners and moisturizers, to skin tints and eyeliners, caps and sweatshirts too.

The combination of content, editorials and forums, and cocreated products drove rapid growth. To the millennial audience, the brand became far more relevant than traditional retail-based cosmetics brands with scientific formulae and Hollywood endorsees.

Emily Weiss has worked with distribution partners around the world, including online retailer Net-a-Porter and pop-up stores in major cities, to bring the online community together in physical places, creating party nights for her local community, talking about the latest skin care products and eyeliner, with added cupcakes and prosecco.

An ecosystem built around a community of consumers, Glossier is now the fastest growing beauty brand in the world. “Our message has always transcended borders and cultures and is central to who we are as a brand” says Weiss.

How brands became ecosystems

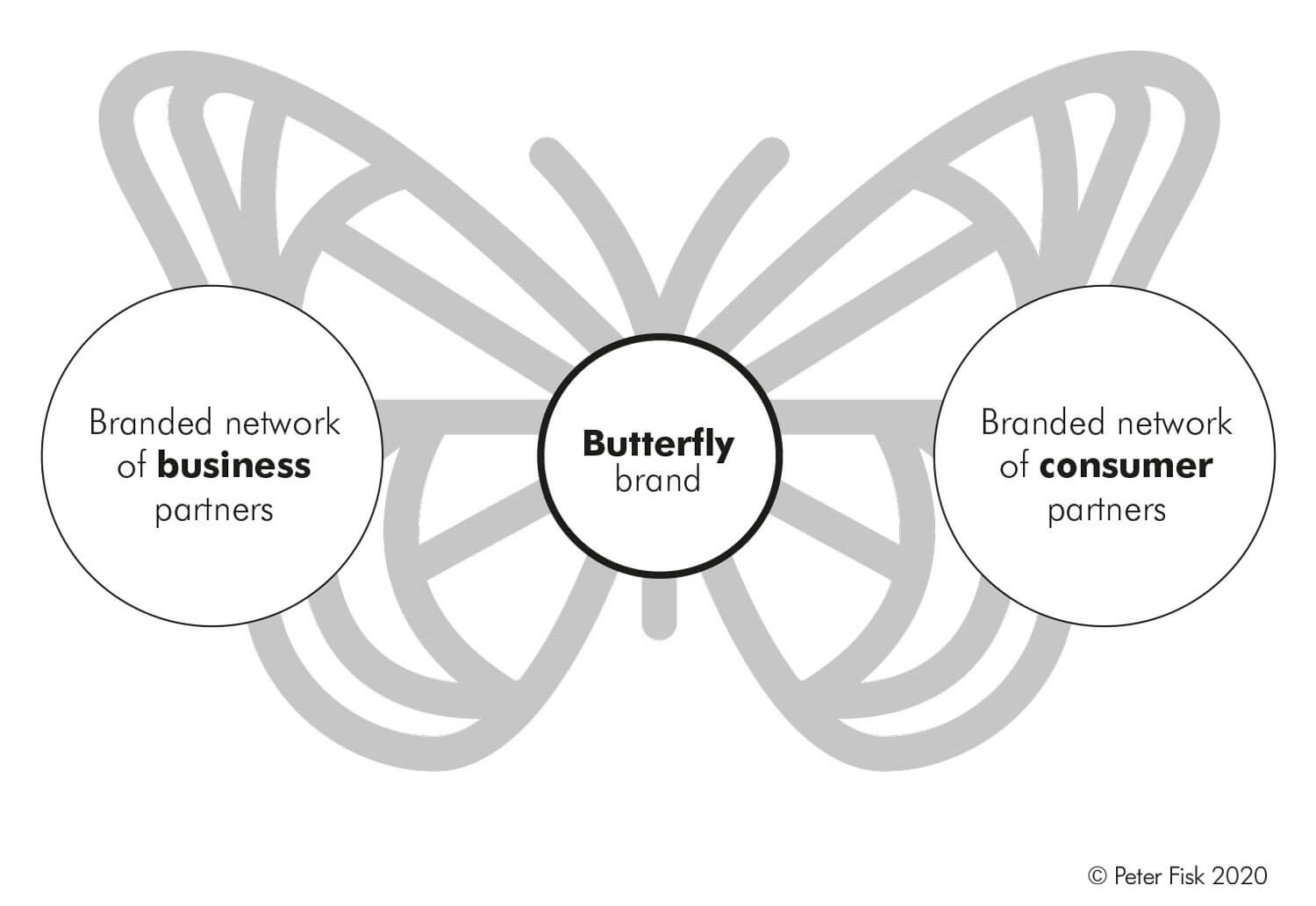

The old idea of brands was that they were marks of ownership. Brand names and identities reflected where they came from, as indicated by the Germanic origins of the word brandt, as farmers burnt their distinctive markings onto their livestock. Most brands initially reflected family names and the activities of those owners.

Over time, consumers became less engaged by origins of ownership, and responded much better to brands that reflected their own lives and aspirations. Names became more abstract, as the concept became more important than the name, and the logo acted as a shorthand for distinctive attitudes and values. Concepts reflecting people, not products, could rise above functionality, and enable brands to move beyond categories.

Digital media further changed the ways in which brands engaged with consumers, ultimately connecting consumers with each other. While greater access to information drove scrutiny and demand for authenticity, consumers responded by trusting brands less. They switched off from listening to overtly commercial advertising, and turned instead to trusting and engaging with friends and others like themselves.

A brand’s story, and ultimately its reputation, became much less driven by what the business said about itself and much more by what people said to each other. In today’s world, brand owners seek to nurture and curate what real people say to each other – tweets and posts, word of mouth, click to click – embracing it as an ongoing narrative that they cannot control but which they still seek to influence and enable. Coca-Cola calls this “liquid and linked” story curation.

Brands today are about communities of consumers who share a common aspiration. The brand doesn’t own the community, but it can be an effective and respected enabler, connecting people, not to buy products per se but to share passions. Products and services then follow, as the brand becomes trusted and aligned to the activity that it enables. A brand purpose is the shared motivation of the community, and its enabler.

Brands are therefore defined more by what they enable people to do, rather than what they do themselves. Brands are more structures of collaboration to deliver this enablement and ongoing relationship, rather than the wrappers of products and transactions. Branded ecosystems provide an effective infrastructure to support this, and ultimately consumers are part of the system too, potentially contributing more to their collective success.

While ecosystems are most often thought of as large virtual networks of supply, they have much more impact when considered from the perspective of demand, how they bring together richer experiences, and reach and connect many more consumers.

The evolution of brands shows how they became ecosystems. The shift from brands of ownership to brands of solutions reflected the shift from brands as a simple device of distinction, of identity and communication, to richer concepts, with added value. Then came the shift to brands of experiences where companies worked together, instead of as “B2B” and “B2C”, to address consumers more collaboratively in a “B2B2C”, or more profoundly as a “C2B2B” relationship, with the consumer in control.

The fourth step, to brands of consumers, is where brands really become ecosystems, leveraging full network effects through collaboration and community, and the predominant relationship is between members, or “C2C.” Glossier demonstrates this dynamic, as does Rapha, the cycling brand founded by Simon Mottram in London’s Covent Garden in 2004 that has spread to over 20 countries. While Rapha has stores where you can buy its premium cyclewear and buy or fix your bike, it is no coincidence that the stores are called Cycle Clubs. There is a membership fee, a coffee shop, showers, and a bike store. They have become the meeting places for people who share a passion.

Ecosystems of technology and healthcare

ARM Holdings started out as a joint venture between Apple, a small British company – Acorn Computers, and VLSI Technology, seeking to build more affordable semiconductors.

One hundred and sixty billion chips later, ARM is owned by Softbank and its Vision Fund, and employs 6,000 people in 45 countries. It provides the technology for 99 percent of the world’s smartphones and tablets, and a multitude of other connected devices.

While Intel used to be the undisputed leader of the market, it ran into problems a decade ago as its sophisticated, but standardised, products couldn’t meet the exacting needs of a fast changing market, where every device manufacturer wanted something different, and quickly. ARM realized that device manufacturers wanted many more custom solutions, responsive to a market that was growing exponentially.

ARM chose a radical business model – not to make any products. Instead it focused on design. And then built an ecosystem of over 1000 business partners around the world who could manufacture its licensed designs fast and responsively to meet the diverse needs of customers and their ever-changing products. ARM’s ecosystem strategy fundamentally differentiated it from Intel, with significantly greater revenues and profitability.

Softbank’s Masayoshi Son acquired ARM for $32 billion in 2016, believing that as the demand for connected technologies continued to multiply, ARM’s ecosystem would enable it “one day to become larger, and more valuable than Apple.”

Similarly, many Chinese companies have grown rapidly by developing ecosystem-based business models – from Alibaba and Baidu, to Tencent and Xiaomi.

These organizations have thrived as ecosystems because they operate in a youthful and flexible environment, young people are willing to rapidly adopt new digital approaches to any kind of activity, and the markets themselves lack structure and convention. WeChat, for example, is the glue that brings Tencent’s ecosystem together. With 1 billion active users, WeChat uses social influence and gaming, to act like a navigation hub for consumers to explore the many dimensions of Tencent’s sprawling virtual architecture.

At the same time, most Chinese ecosystems are privately owned, allowing them to make more strategic investments without having to deliver short-term returns. There are fewer regulatory hurdles – for example, in using customer data and in entering a new market.

PingAn is a great example of taking the ecosystem model further. Whilst it started out as an insurance company, founded in 1990 and now completely publicly owned, it has used this financial underpinning to support its growth into many other sectors. A little like Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, it has built on its financial powerhouse, but in its case by using new technology platform thinking. With a market value of over $200 billion, it is already one of the world’s top 10 largest companies.

Good Doctor is PingAn’s digital healthcare business, established in 2015, and now the world’s largest healthcare platform with 300 million users. It describes its service model as “Internet + AI + physicians,” which translates as an online app through which a patient will initially evaluate their health or specific condition using an AI-enabled diagnostic. If required they will then be connected by video call, typically within an hour, to a real doctor, most likely one of 10,000 employed by PingAn who sit in its service hubs.

The doctor can then refer their patient for further diagnosis, treatment, or medication. This is when the ecosystem of partners becomes invaluable with its nationwide network of clinicians, hospitals and pharmacies, and even a home delivery service for prescriptions. The platform also offers wellbeing advice for health and wellbeing – for example, supporting new mothers and the elderly. A monthly subscription embraces an insurance fee to cover some costs, whilst a premium service called Private Doctor offers additional services and all-inclusive fees.

How ecosystems became brands

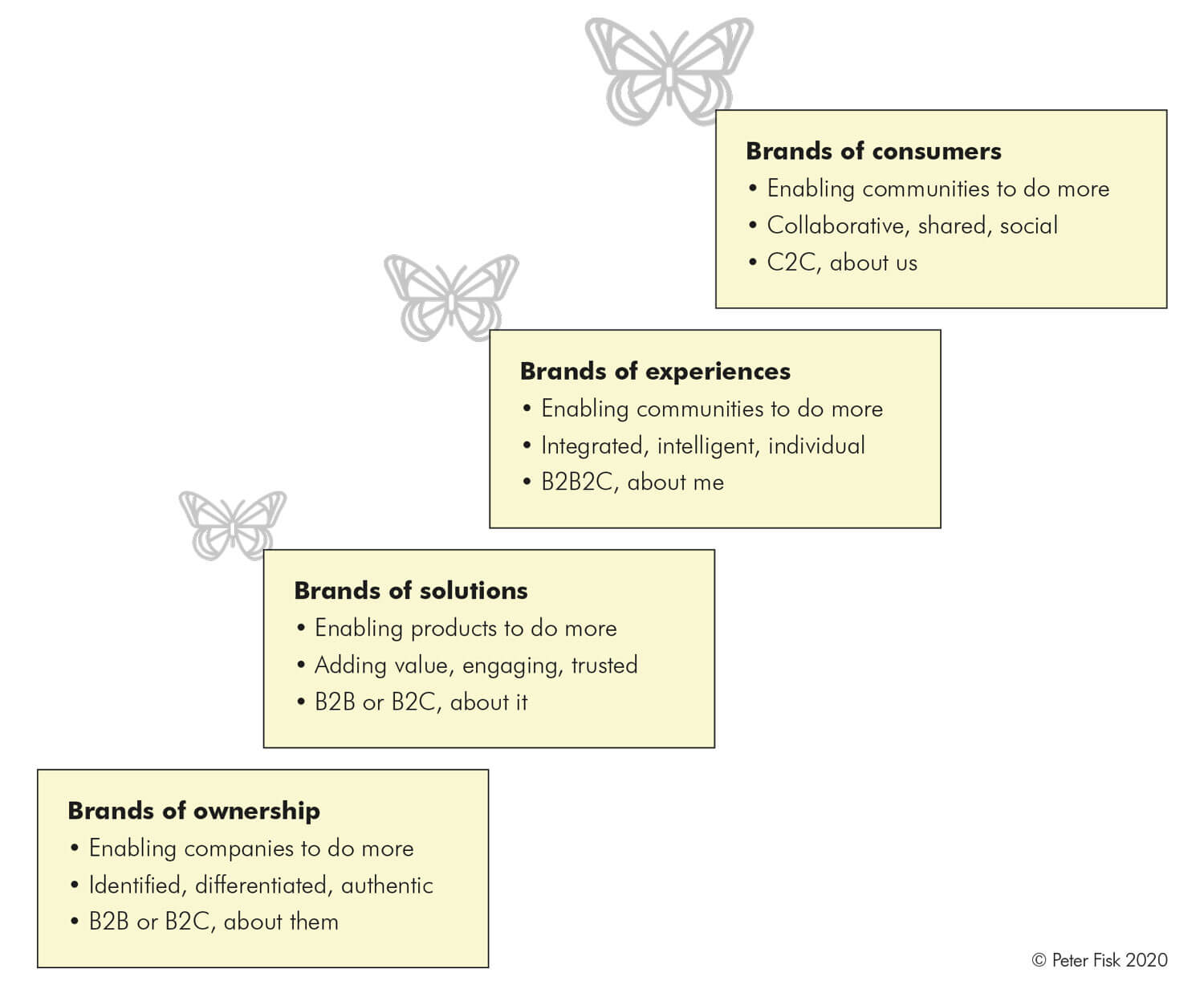

Ecosystems have evolved in a similar way to brands, and there is an interesting correlation between the four phases of each evolution.

GE has long been an ecosystem of many partners, however, Jack Welch’s mindset was to keep as many of these under his corporate umbrella as possible. As organizations took a largely capability-driven and efficiency- minded approach to success, they tried to build increasingly diverse networks and collaboration between areas, but largely in-house.

That changed with the technology revolution, with companies like ARM recognising that the accelerating speed of progress required more agility, but also that risk could be shared, and that capabilities were no longer the foundation for growth. They looked beyond their organizations for support, and became partnered ecosystems.

Virgin is a great example here. I remember founder Richard Branson telling me that one of the so-called “truths” of business that he disliked most was the convention to focus on what you’ve always done. He of course had little idea how to run an airline, a bank, a media business, or a spacecraft when he launched each of them, but always with a partner who knew what they were doing.

Indeed, Virgin’s approach is not so dissimilar from Mikkel Bjergso’s. Branson’s company is essentially a venture capital business that gets involved in many new businesses, usually with only a small investment. Part of the deal, however, is that the new business licenses the Virgin brand – Virgin Media, for example – from which Branson gains a royalties stream. This has proved massively lucrative for him.

The most dramatic evolution comes with the shift to experiential ecosystems, where the dynamic flips from partners driving efficiency to serving customers in better ways.

Haier, the Qingdao-based home appliances manufacturer, is a great example here, recognizing that it needed to think in consumer-based categories, rather than technology-driven product categories. Haier’s distinctive RDHY operating model, built up of thousands of entrepreneurial micro-businesses, enables it to work with partners and consumers much more easily. A focus on connected devices, or Internet of Things (IoT), drives it to reimagine how entire activities can be innovated – shopping, clothing, driving, and entertainment. Haier’s clothing ecosystem, for example, reimagines how people can buy, clean, wear, store, and even recycle their clothing in radically better ways.

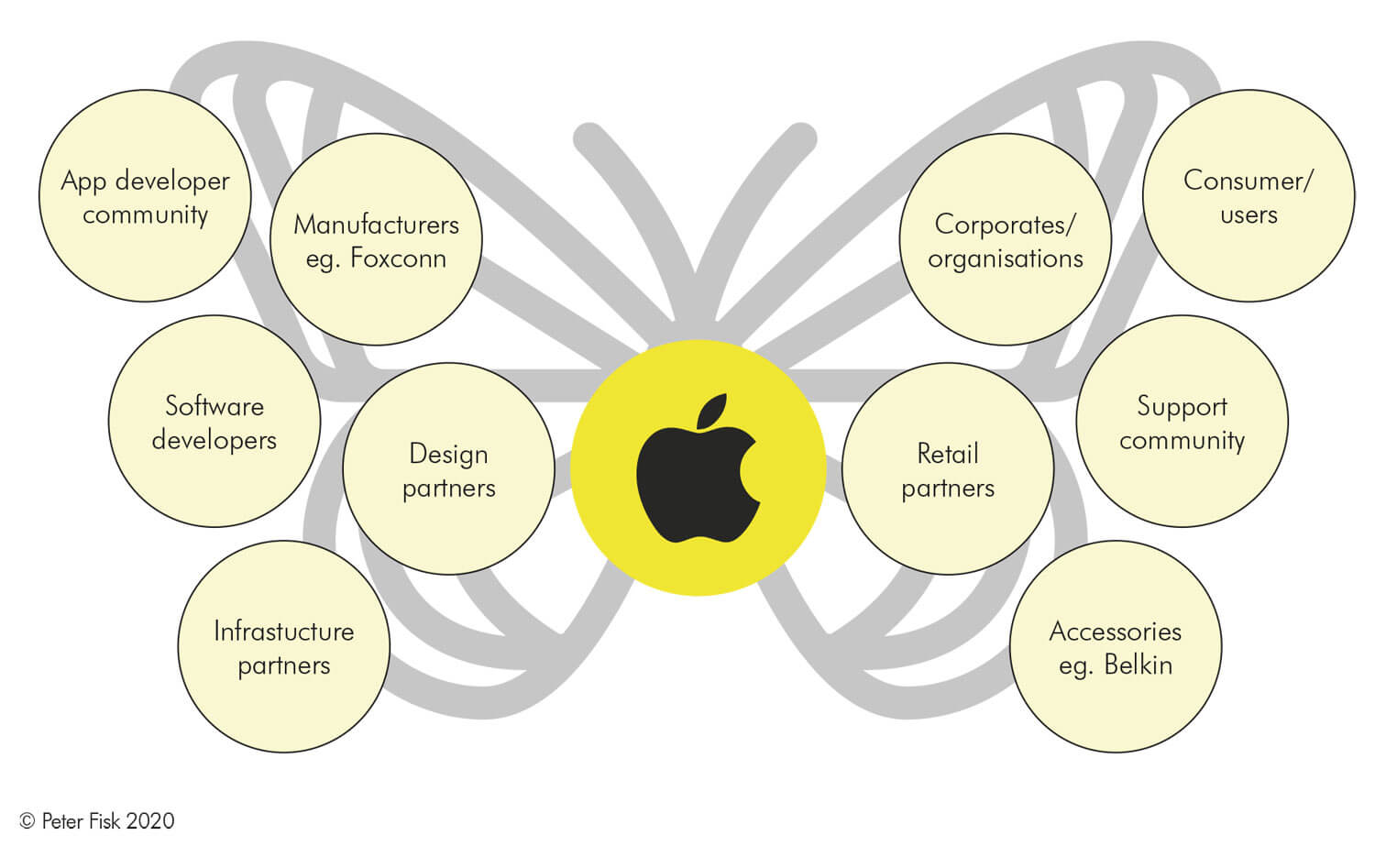

The final step is to build the ecosystem not around the business, the product, or even the category, but around the consumer. Mikkeler and Glossier are good examples, as is Apple.

The most important shift in Apple’s thinking under Tim Cook has been towards a much more consumer-centric approach to the role of devices, how they work together, and more importantly the content that they support, and activities that they enable.

Apple’s business model today is brand-centric, creating integrated experiences for consumers that enable them to connect with each other and their wider worlds. The synchronicity of Apple devices has become a joyful simplicity, and the wonders of its app store, created by millions of partners, has made the experience far richer.

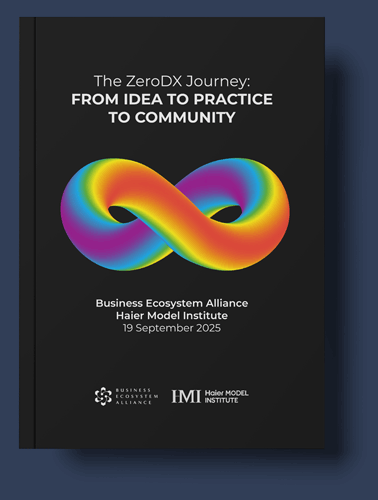

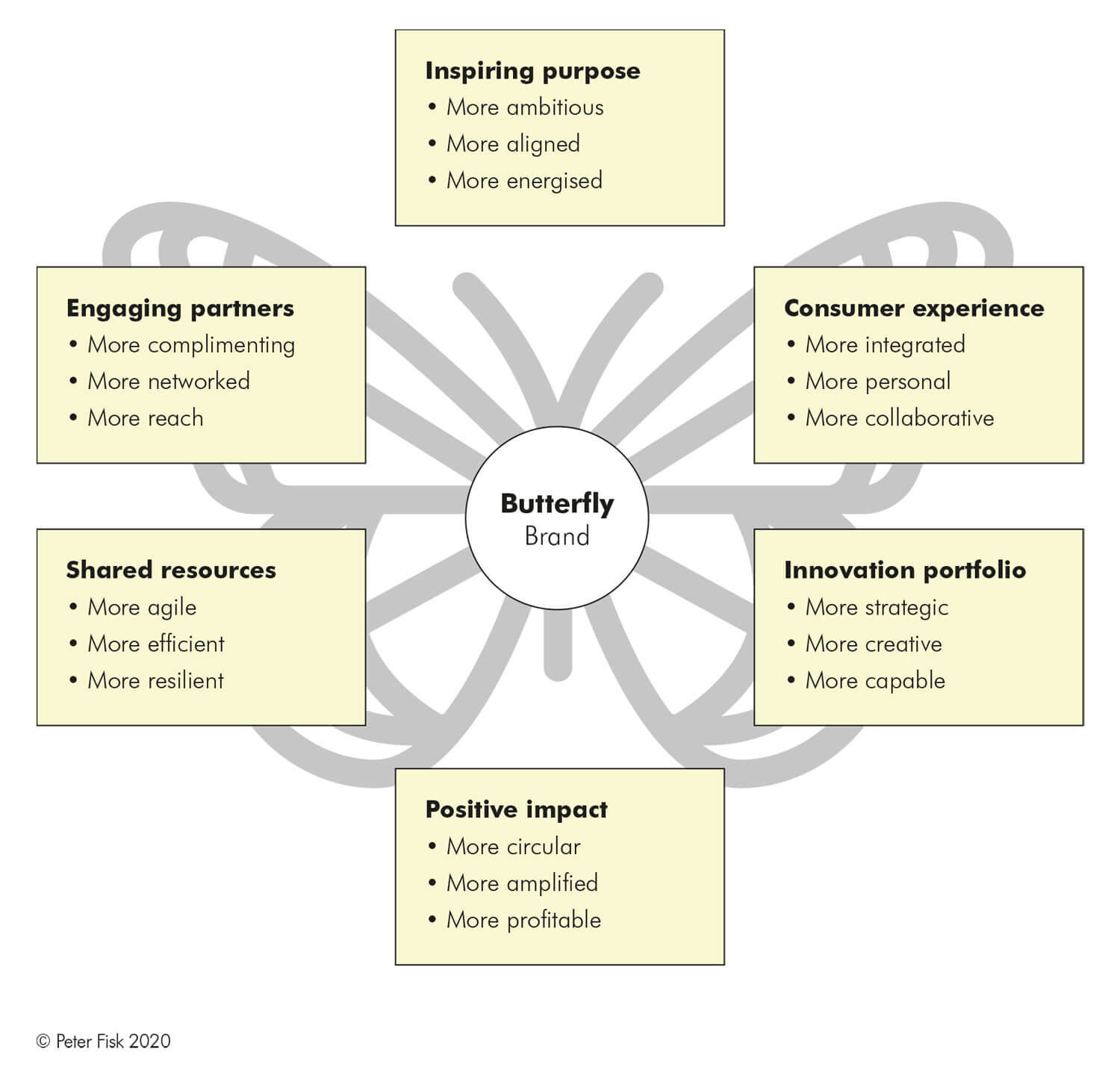

Building a butterfly brand

A “butterfly brand” is a relatively small business with a big imagination, which succeeds by bringing together a distinctive ecosystem of partners, enhanced by a powerful and engaging brand reputation.

The butterfly brand can achieve dreams whilst staying small and highly agile, using its partners with complementary skills, shared risk and reward, to add reach and richness, to have more influence and impact. Indeed, you could add many other examples, from Airbnb to Uber, of asset-light companies succeeding through ecosystems.

What makes butterfly brands special is when they go beyond the conventional thinking of ecosystems.

In Business Recoded I evaluate the 49 new codes required for business to succeed in today’s rapidly changing world: to explore changing markets, embrace new disruptive technologies, address the most urgent environmental issues, and resolve the fractures between business and society; to embrace purpose beyond profit, stakeholders beyond shareholders, and futures beyond those imaginable today.

Applying these codes to the butterfly brand, we start to map out a simple but better checklist for the ecosystems of the future.

The butterfly brand, which could be a start-up or an established business, comes together with its partners not simply in pursuit of financial gain, but with a shared purpose – an inspiring collective ambition, by which all the partners together can contribute towards a bigger goal, and potentially a better world.

A strong common purpose creates shared direction, and an aligned culture.

The butterfly brand operates together with its partners much more closely, in a shared business model, one which efficiently utilises shared resources, while also having the agility to morph over time. It delivers a better

experience for consumers, working together to design and develop innovative solution-based experiences, and then delivers them in a seamless, more personal, more responsive manner.

And most of all, the butterfly has a more positive impact, financially and beyond.

Driven by its purpose it seeks to achieve more than profitable gain. Through a coordinated and “circular” approach, it brings together a system-based approach to resources that deliver zero net waste. Or even better, achieve positive net impact.

Finally, we should remember “the butterfly effect,” famously coined 50 years ago by Edward Lorenz, a nature- loving meteorology professor at MIT.

While seeking to simulate weather patterns using a computer model based on 12 environmental variables, Lorenz entered some numbers. He realized that the smallest of differences in numbers, going down to many decimal places, could make a huge difference to the weather prediction.

Likewise, the business leader of the butterfly brand can make huge differences to the positive experiences of consumers, the mutual success of every partner, and to the continued evolution of the branded ecosystem.

Peter Fisk’s career was forged in a superconductivity lab, accelerated by managing supersonic travel, shaped in corporate development, evolved in a digital start-up, and formalized as CEO of the world’s largest marketing network. He leads GeniusWorks (www.theGeniusWorks.com), a strategic innovation accelerator based in London, and is a professor of leadership, strategy and innovation at IE Business School in Madrid, where he directs its flagship executive programme. He is the author of Gamechangers and Business Recoded.