Ecosystemic evolutions: organizing beyond boundaries

Simone Cicero

As we enter the third decade of the twenty-first century, organizations face stunning challenges. New risk factors are rising and unpredictability in our societies and economies is becoming constant – as the Word Economic Forum anticipated in its Global Risk Report 2020, “turbulence is the new normal.” And that was before the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

Business ecosystems – with their capacity to quickly reorganize in networked fashion and to leverage an emerging niche speciality – offer new organizational perspectives and, at the same time, are truly changing the nature of the corporate organization to an extent that is hard to yet quantify. It is increasingly clear that the profound need to move away from the linearity of twentieth-century business lines and value chains will require a structural reinvention of the theory of the firm and, to some extent, of its raison d’etre.

Two powerful trends are at work. On one hand, there’s the radical re-prioritization of user perception of value as we saw in early 2020 with the coronavirus outbreak; on the other, rising unpredictability. What will be the impact of such trends on the optimal shape of the organization?

Adopting a Conway’s Law lens

Conway’s Law says: “any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.” It is something I often refer to when describing the evolution of platforms and organizations. To be able to thrive in a truly post-industrial, networked ecosystem- led world, an organization needs to mold a new design.

Being able to look through the Conway’s Law lens will take on a new level of importance as two major trends emerge. First, working practices evolve towards much more distributed patterns of work. (As Mary Meeker noted in her early reflections on the pandemic, most companies believe that “after the experience of forced remote work – they will shift to more distributed work.”)1. Second, value chains will need to be reorganized to work differently across regional geographies, to ensure better resilience and less dependence on supply chains that in the mind of policymakers and national leaders have “gone too far.”2 New organizational players and entrepreneurial opportunities will rise to play a fundamental role in the creation of a somewhat less “efficient” and “just in time” economic paradigm. This new paradigm will favour value chain elements that, on the one hand are more directly bounded regionally and, on the other, feature alternative routes for the sourcing of needed components and contributions to key processes. In the transformation, multinational organizations will need to rethink their organizational structures and brands will need to adapt to play a role.

If we focus on the remote work dimension, for many types of companies – such as startups and software development firms – widespread lockdown and “shelter-in-place” orders did not constitute a big break in terms of workflow and organization. A great deal was already done remotely and asynchronously. For many more traditional players, this new situation radically changes the way work is organized. Clear and well-structured communication becomes essential to allow teams to carry out their work efficiently. This may result in increased autonomy and distributed work. As organizations go fully online and remote this may end up reshaping them beyond simply a matter of on- or offline work.

Consider Amazon, which is often depicted as “probably the best-known case of a divisional organization” and “one of the clearest case manifestations of Conway’s Law.”3 Besides its well-known divisional model – with divisions looking after specific product offerings such as AWS or Kindle, or macro-parts of the business such as publishing – the main advantage of Amazon resides in its radical policies in new business creation and its internal communication structure.

As depicted by Benedict Evans, Amazon has two main platforms – an e-commerce one and a logistics one – and on top of those, a radically decentralized machine: atomized teams sitting on a standardized common internal system.4 This loosely coupled structure comes from a now iconic choice that Bezos and the company leadership enforced in the early days: they broke down functional hierarchies and restructured into small, autonomous teams, small enough that they could be fed with only two pizzas. This gave them extreme autonomy and the obligation to operate and communicate with each other in an asynchronous mediated API.5 In the words of Evans, this structural decision on organizational architecture produced three main effects: virtually infinite scalability, a tendency to reach the lowest common denominator in the product buying experience, and the substantial equivalence of internal and external units with regards to the contribution to the business model. In Evans’ words, “the constraint to the model’s growth is how fast you can hire product teams and sign supplier agreements, letting other people do it for you and charging them a margin (and of course the internal teams also have margin targets too) lets you scale faster and with less risk.”

Mass collaboration, loosely coupled

Allowing mass collaboration to happen at scale between loosely coupled units emerges as a pattern in modern competitive organizing, not only in terms of internal communication but also in the massive transition we have seen emerging for almost a decade. There is a continuity between the adoption of platform business models that secured the success of companies such as Airbnb or Shopify and the reinvention of the organization through pervasive P&L and radical divisionality. The common denominator of this transition is the acknowledgement of the plummeting of transaction and coordination costs and of the possibility to substitute complicated business processes – typically managed through bureaucracy – into software as a service.6

A good example of this may be found in the health and social care company Buurtzorg. Dutch entrepreneur and Buurtzorg CEO Jos De Blok has explained how the company effectively “transformed bureaucracy into software” and in this way empowered a network of nurses. This helped create a holistic healthcare context around the patients by leveraging collaboration with surrounding networks. Buurtzorg professionals “attune to the client and their context, taking into account the living environment, the people around them, like a partner or relative at home, and on into the client’s informal network; their friends, family, neighbours and clubs as well as professionals already known to the client in their formal network.” This is supported by a set of software and coordination tools that the company built to let the work being organized at the edge, beyond control and micro-management, move towards full independence and self-organization.

In the application of such an outside-in pattern of organizing, defining the boundaries of the organization becomes a complex and, to some extent, unhelpful task. Allowing outsiders to get involved, becoming insiders – as transaction costs plummet due to technology – becomes of paramount importance to the creation of an organization that can facilitate patterns of networked collaboration, self-organization and the blurring of boundaries. To allow external contributions to the business model, and the innovation process, becomes a key competitive edge: as Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Maximilian Schüssler of BCG have noted: “Ecosystems compete on their degree of openness.”7

The case of China’s Haier Group is emblematic: not only are employees incentivized to start their micro- enterprises (adding a node in the internal network) as a way to facilitate fast and frequent interactions with consumers, but also companies outside the group are allowed into the competition for providing services to the micro-enterprises. The company has also created a new organizational artefact called the Ecosystem Micro Community (EMC). The EMC is a self-organized and self-led coalition of enterprises coordinated by the emergent leadership of one micro-enterprise. This is powered by an EMC contract based on a smart contract allowing the fast implementation of rules of collaboration based on shared objectives (smart goals), creatively taking the added value of the user experience as the goal and driving force of the contract, and committing resources for the achievement of them. In a sort of fractal platformization pattern, the very business model of the most of the innovative micro-enterprises also leverages independent producers and professionals. A good example is the online logistics marketplace Goodaymart (that attracted investments from other groups such as Alibaba), where many independent logistic providers are organized through a technological coordination platform.

Ecosystem enabling

Despite fragmenting an organization into small nodes, molding it with its broader ecosystem and facilitating the creation of means of communication through software interfaces – rather than a bureaucratic process – is the core of the role of organizational leaders in an ecosystemic organization (epitomized by Jeff Bezos and Haier CEO Zhang Ruimin.) Ecosystems become, in the words of Simon Wardley, “future sensing engines.”8 As Wardley explains, the organization not only needs to enable coordination between the nodes of the ecosystem but also needs to create tools to allow the players in the ecosystem to innovate with a lower risk of failure. These tools – in the form of enabling blocks and services – will be used to create new value propositions, sitting on top of the enabling ones in the value chain. As a key and complementary responsibility, eventually, the ecosystem-enabling organization must act to standardize the novel value propositions emerging from the periphery, institutionalizing innovations for broader adoption, pushing the ecosystem entities to develop new propositions, on top of the newly standardized ones. The organization’s reference ecosystem appears to be the most effective means for an organization to move – as in Lisa Gansky’s words, from the “no more” to the “not yet.”

In the continuous Innovate-Leverage-Componentize cycle that will result from this virtuous circle, the organization will transform emerging innovations into: either modular elements for the rest of the ecosystem to start again to build upon or, will take over the complexity of vertical integration and create the strictly necessary functional organizational structures for the production of more “industrialized” or “curated” experiences that may need management cultures, processes and infrastructures that don’t necessarily overlap with a loosely coupled marketplace-based structure.

The application of such a mechanism of unbundling and rebundling is not new and has been thoroughly explained – for example by Ben Thompson. He explains the pattern as follows: “breaking up a formerly integrated system – by commoditizing and modularizing it – destroys incumbent value while simultaneously allowing a new entrant to integrate a different part of the value chain and thus capture new value.”

In many examples, organizations modularize a basic element of the value chain that was previously integrated, then reintegrate an upper layer of the value chain by controlling it, often favouring aggregation through the attraction of now modularized parts of the value chain, often in the form of independent ecosystem players (such as property owners in Airbnb or content producers in the case of Netflix). Such ecosystem players will effectively reshape to optimize their interaction within the interface that the organization provides. As an example, Rent the Runway and other clothing rental services are contributing to reshaping the ecosystem around fashion design, as designers become less focused on getting their clothes into department stores than to distribute them through rental and subscription-based platforms.

In this recurring pattern, organizations first modularize a specific part of the value chain (inventory in the case of direct to customer marketplaces, teams able to produce entrepreneurial ideas for market-facing innovations in the case of Haier’s or Amazon’s organizational structure), providing clear rules and interfaces for engagement. Later, as the “disobedient” and independent ecosystem players create something radically new that attracts customers and needs to be scaled-up, these innovative propositions are integrated vertically into the platform’s core set of services – or practices.

As an example, Airbnb captured an emergent behaviour of co-hosting among its users (third parties managing properties in the place of busy hosts) and successfully vertically integrated a set of tools for co-hosting in the platform. This provided a more consistent experience, and further modularized the co-host role for better scalability. Similarly, Haier micro-enterprises sometimes scale so quickly that they take on the role of platforms, taking over responsibility for integrating parts of the services, enabling further their reference ecosystem of third parties, including other micro-enterprises that are still in earlier stages of maturity.

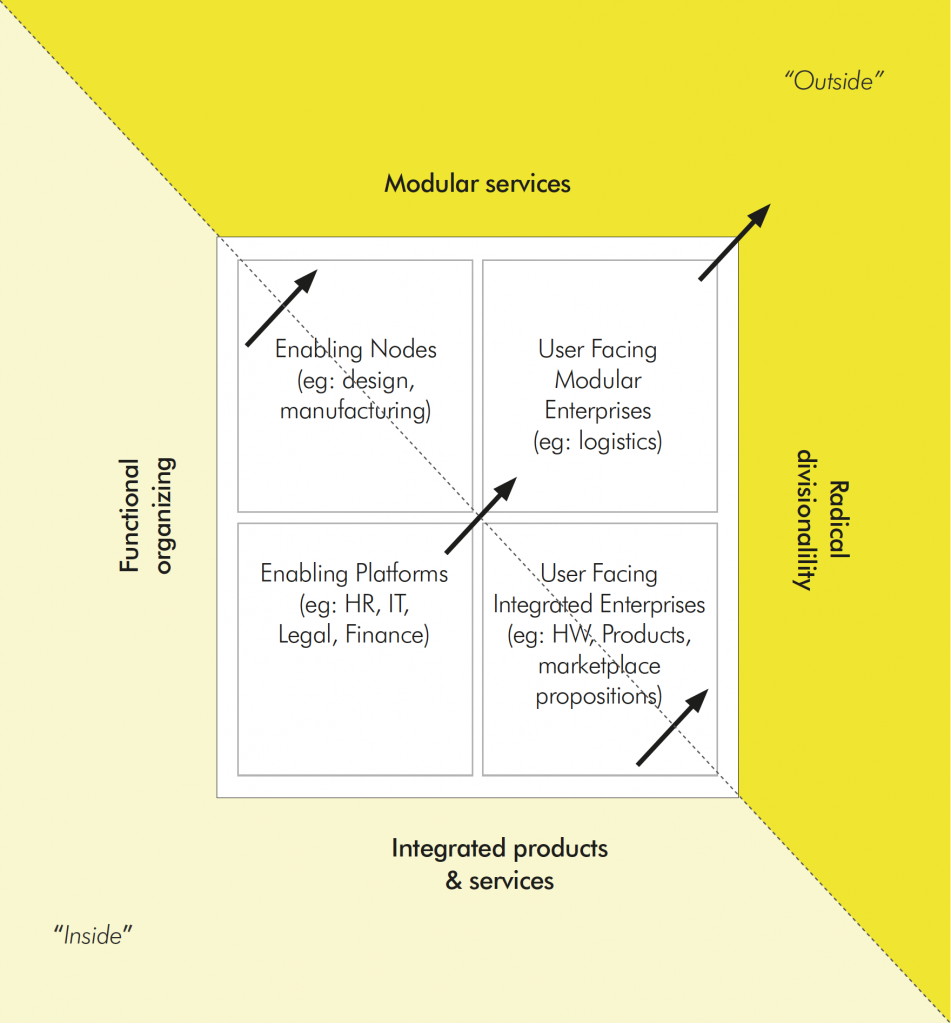

It appears then that a modern ecosystemic organization needs to be able to play on the full spectrum of management and organizational models from customer focus to ecosystem services, from modularized to integrated products, from radical divisionality (such as with Haier’s micro-enterprises and Amazon’s two-pizza teams) to functional integration in the form of supporting platforms providing basic services such as scalable manufacturing or HR, as in Haier’s case.

What’s next?

The impacts of such a transition towards divisional organizations and more modular products (and services) may be far-reaching. The COVID-19 outbreak seems to have exacerbated the speed of change but needs to be framed as a harbinger of times to come, with unpredictability becoming a structural aspect of our economies. This growing unpredictability seems increasingly hard to manage by traditionally functional organizations.

Functional organizations (where profit and loss are centralized and units are distributed according to key support functions such as marketing and HR) are great at producing “integrated” product experiences. These companies evolved in the industrial age and can ensure coherence more easily when needed, thanks to vertical chains of command. When product management nails it, functional organizations can bring innovations to the market not only quickly but also with a relevant quality of experience. By doing so they often achieve network effects, economies of scale, and strong advantage positions that allow them to capture a somewhat unfair value over the long term. But, their success often protects pockets of inefficiency. The vertical integration of products and services effectively impedes competition from happening at any of the product layers.9

Functional organizations and integrated products might be – in light of this – more fragile to rapid and continuous change, due to unpredictable phenomena that may cause supply chain or value chain disruptions or even just deep – sometimes unexpected – behavioural changes. To build more antifragile capabilities in society, economic paradigms appear to be shifting back towards more locally-redundant and unbundled business processes where pieces and players are more interchangeable and continuity of service can be ensured more easily during disruptions. Functional organizations, with their need to vertically integrate, protect, and control the whole chain may fail to maintain their organizational structure in such a context, due to the constraints and rigidities they accumulate.

Despite proving to be more adaptive to local and contextual conditions, more flexible and more organic, even organizations that are divisional but with substantially large and bureaucratic “divisions” may end up suffering the same adaptability issues. Emerging trends of organizing have pushed organizing towards more networked structures with smaller, networked divisions whose interactions are mediated through different types of artefacts, normally providing enabling services (platforms). To some extent, such a direction of organizational evolution can be seen through the lenses of David Ronfeldt’s seminal work on the TIMN (Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks) framework as these four stages are mirrored in the theory of the firm.10 As society transcends markets and networks take hold as the main creation, production and governance means – a manifestation of the maturation of the information age – that human organizing, in interplay with its changing context, is embracing the network structure.

The trend that brought us individuals and then teams networked through emerging organizational artefacts (such as Haier’s platforms) inside the same firm, is starting to move in a new direction that goes beyond the single organization towards a widespread collaboration between organizations. At societal level, Haier’s Enterprise Micro Community, by including organizations inside and outside of the group, is a signpost in this evolution. As John Hagel explains, evolutionary pressure will push an organization’s customer (or more broadly, a user) to look for flows of value creation that go beyond a specific vendor, beyond a specific organization, and reach the possibility to create value with anyone, everywhere.11 This will also, in turn, push the entities connected to the ecosystem on the production side to shapeshift, to remain able to produce value in exceptional times when markets are reshaped in an unpredictable way. The case of the dark kitchens emerging to serve customers without a publicly open shop during the COVID-19 pandemic seems iconic of the change.12

The markets of the age of networks may end up being made by a plethora of smaller, more independent, small scale organizations, all interconnected through new means of communication that are also quicker to reconfigure. Organizational nodes become smaller while at the same time more powerful and more specialized in their niche, more transient and more adapted to the dynamics of a “fluid” society, the society of the information age. In this context, a new theory of the firm might be emerging to confront the crisis of capitalist governance as the “limits of using enclosure as a tool of capitalist accumulation” become clear in a small world where externalities are quickly exacerbated and globalized.

As a result, an effective organizational theory – and praxis – for the post-industrial and perhaps post-capitalistic age, may need to be heavily based on relationships and systems thinking, and feature an unbounded way of relating to the commons that don’t separate between in-groups and out-groups.

More than thinking about the evolution of a single organization in an ecosystem, it appears that – accelerated by the pandemic, and more generally by the resurgence of unpredictability in our economies – we may be witnessing the dawn of a new age of organizing. The developments of this new wave will happen within a firm but also in the space between them, from individuals to communities to bioregional playgrounds, states, and civilization, and in the realm of fluid cooperation for a world in constant flux more than at the scale of single market opportunities and in the groove of competition.

Zhang Ruimin said: “Companies are going to disappear, while organizations won’t.” We can probably generalize this thought more clearly by saying: “companies will disappear, while organizations won’t (and the new organizations will be self-driven).” More research is needed. We do not yet know what the future of organizing will look like, but this future is approaching faster and faster each day. As my friend Tomas Diez once said: “Future is a word of the past.”

Simone Cicero is creator of the Platform Design Toolkit (platformdesigntoolkit.com). He is a member of the 2020 Thinkers50 Radar listing.

Special thanks to Stina Heikkila for the editorial review and strong contributions to the text.

Footnotes:

1 D. Primack, “Exclusive: Mary Meeker’s coronavirus trends report”, Axios, 2020; https://www.axios.com/mary-meeker-coronavirus- trends-report-0690fc96-294f-47e6-9c57-573f829a6d7c.html

2 PIIE, “The pandemic adds momentum to the deglobalization trend”, 2020; https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues- watch/pandemic-adds-momentum-deglobalization-trend?fbclid=IwAR1QJ-nC0-W82jPrzAas0yVdkJV8H0v8mu7V1uwj9LqpFsGn5 M8IyfQ3mIw.

3 Leonardo Federico, “The single most important internal email in the history of Amazon”; https://www.sametab.com/blog/ frameworks-for-remote-working.

4 Benedict Evans, 2017; https://www.ben-com/benedictevans/2017/12/12/the-amazon-machine?utm_source=Benedict percent27s+newsletter&utm_campaign=a0036b241e-Benedict percent27s+Newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_ term=0_4999ca107f-a0036b241e-70378189.

5 Allthingsdistributed.com, “Modern applications at AWS - All Things Distributed”, 2019; https://www.allthingsdistributed. com/2019/08/modern-applications-at-aws.html.

6 Geoffrey Moore, “The Nature of the Firm—75 Years Later”, 2015; https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/articles/the-nature-of-the- firm-75-years-later/.

7 https://www.bcg.com, “How Do You ‘Design’ a Business Ecosystem?”, BCG, 2020; https://www.bcg.com/publications/2020/ how-do-you-design-a-business-ecosystem.aspx.

8 Simon Wardley, “Scenario planning and the future”, org; https://blog.gardeviance.org/2014/06/scenario-planning- and-future.html; “Understanding Ecosystems”, Gardeviance.org; https://blog.gardeviance.org/2014/03/understanding- ecosystems-part-i-of-ii.html; “On Platforms and Ecosystems”, Gardeviance.org; https://blog.gardeviance.org/2015/08/on-platforms-and-ecosystems.html.

9 This is well explained in Thompson and Allsworth’s podcast mentioned earlier and in: Ben Thompson, “Integration and Monopoly”, 2019; https://stratechery.com/2019/integration-and-monopoly/.

10 David Ronfeldt, “Tribes, institutions, markets, networks: a framework about societal evolution”; https://www.rand.org/pubs/papers/ html

11 John Hagel, “The Big Shift in Business Models”, Marketing org, 2016; https://www.marketingjournal.org/the-big-shift-in business-models-john-hagel/.

12 Cummins, “Dark kitchens in high demand as isolation boosts delivery services”, The Sydney Morning Herald, 2020; https:// www.smh.com.au/business/companies/dark-kitchens-in-high-demand-as-isolation-boosts-delivery-services-20200409- p54imu.html.