Ecosystems: the how factor

Alessandro Di Fiore & Elisa Farri

Ecosystems are the flavour of the organizational month. But, amid the hype and hyperbole, there is often a dearth of real-life organizational experience and wisdom. In the end, all that matters to executives is whether ecosystems could benefit their organization and, if so, how best they can make those benefits a reality.

There is an urgent need to cut through the theories and examine what actually makes ecosystems work and why some work better than others. In our consulting work, we have witnessed a gulf between theory and practice. Executives understand the opportunities that ecosystems offer, yet they need guidance on the How.

The start of this process must be a realization about what an ecosystem actually is – and isn’t. The most common misconception is that an ecosystem is simply a bundle of integrated products and/or services that can be sold or cross-sold. In this view, an ecosystem is made up of a set of products and/or services that have been selected by the company in its core market or industry. An ecosystem is simply more of the same, an accidental confluence of products and/or services.

The reality is – and has to be – different. As defined by London Business School’s Michael Jacobides (see his piece later in the book), an ecosystem is a basket of multiple options of services and products across several markets or industries and offered by multiple entities. In ecosystems, firms collaborate – to a greater or lesser extent – so that they can together offer greater choice and value to end-users. From the multiple options on offer, customers can make better choices. Most of the time, though not always, an ecosystem comes with a digital platform.

The attraction of ecosystems is that they deliver value in two ways. First, they make competition less relevant. Typically, ecosystems beat products because they create more value for customers by offering a greater variety of goods and services, while reducing the associated transaction costs. They are, as a result, a powerful means of escaping the process of commoditization that inevitably happens in product and service competition over time.

When Tencent launched WeChat in 2011, the idea was to offer a mobile messaging application. As WeChat’s user base grew exponentially, Tencent benefitted from powerful network effects and gradually added complementary services to generate more valuable customer interactions. The keystone was the launch of WeChat Pay in 2013. Thanks to the fast adoption rate of the new payment service, Tencent was able to attract partners and integrate new services: from ride-hailing app Didi Chuxing, to Tencent Music, food delivery platform Dianping, and bike-sharing service Mobike. But the complementor that is revolutionizing the WeChat ecosystem is WeChat Mini-Programmes, allowing a range of new services from over 200 industries. WeChat users can now buy products and perform many other tasks without ever leaving the app. With an all-in-one click, Tencent has expanded the WeChat basket of products and services exponentially.

Second, ecosystems create customer stickiness by design. Usually, when you enter an ecosystem as a customer there is a friction or value loss in leaving the ecosystem. By taking advantage of customer information flows and data, more value can be created thanks to more customization and modularization.

Amazon has used this strategy very effectively. Its Prime Membership offering has a 93 percent retention rate after the first year and 98 percent after two years. The secret sauce of Amazon’s ability to break the code of customer retention is its ongoing effort to raise customer expectations of personalized experiences. Customers are attracted by more convenience and personalized experiences, and the more personalization succeeds, the more precise the data Amazon has at its disposal.

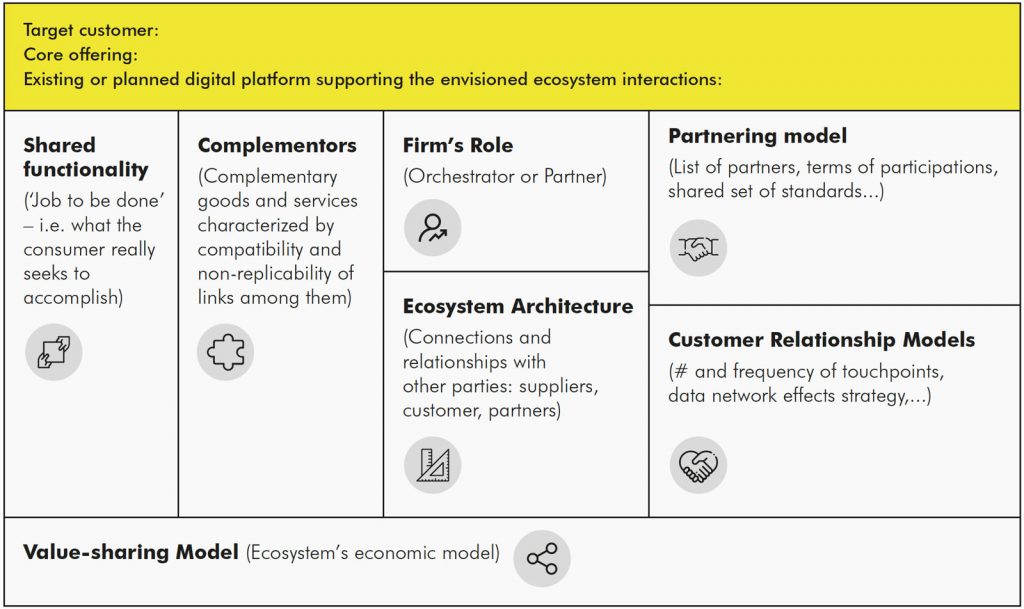

In our work with companies throughout the world, as they seek to maximize the value from the ecosystems they are involved in or develop new ecosystems to grow their business, we have identified the following elements that need to be properly designed and executed to make the ecosystem strategy work:

- Starter questions

The fundamental questions that have to be answered are: Who is the ecosystem’s target customer? What is the core offering of the firm on which the ecosystem development strategy must be built? And, what is the existing or planned digital platform that could eventually evolve and support the envisioned ecosystem interactions?

The ongoing challenge is to focus on the core starting point on which to build the future ecosystem strategy, rather than on everything that could be integrated or connected. Drifting away from a simple and very focused core starting point is a common trap into which executives tend to fall when they start formulating their ecosystem strategy.

An agrochemical company we worked with defined its target customer as what it described as the “modern farmer segment.” Its core offering covered crop protection products and its digital platform had been developed with a farm management online service. By leveraging its existing core and developing it more accurately to reflect the new strategy, the company was able to create a powerful ecosystem.

- Shared functionality

To borrow from the late Clay Christensen: What is the ecosystem’s job to be done? What does the customer wish to accomplish through their interaction with the ecosystem? There is a hidden danger here that a too narrow job to be done is identified. This might focus only on a single product or service of the firm with the aim to be the orchestrator. To combine successfully with other goods and services, the job to be done must be wide enough to create value for the customer by providing access to an ecosystem’s basket of products and services.

Often, a narrow job to be done is widely understood in the organization. This is the problem the company solves for customers with their existing products or services. Widening the aspiration involves a holistic analysis of the customer’s experience cycle. Once the customer’s interactions with the organization are more thoroughly understood, the assumed job to be done of the envisioned ecosystem can be visualized.

For our agrochemical client the process of looking at the job to be done proved a real eye-opener. Its fundamental belief was that farmers were focused on protecting their crops from insects, diseases, and so on. The job it was doing was helping farmers achieve this objective. Talking with farmers it became clear that this was way too focused and actually missed the big issues on the farmer’s agenda. The agrochemical company recalibrated its job to be done, built on the realization that farmers want to maximize crop yields and profits while protecting themselves from risks.

At an early stage, it is critical to be customer-centered in building a compelling case for the job to be done. Only after you excel in providing an exceptional customer experience can you seek to broaden your ecosystem to include other third-party complementors.

- Complementors

Are the ecosystem’s products and/or services complementary to each other? Are they characterized by compatibility and non-replicability of links between them? One approach to this is to first compile a long list of potential high value complementors. Look at the value they provide for customers and the ease by which they could be integrated. Next, test how the complementors could multiply (not simply add) value. Ask whether a complementor leads to additional customer value? Does it significantly increase customer interactions and engagement? And what else could be added?

For the agrochemical company this meant looking further afield than simply providing chemicals to customers.

It moved into agronomic services, such as soil data and mapping tools, as well as risk management services including insurance and risk protection. In the process of adding these new services, the agrochemical company expanded the scope of its business and brought new complementary products and services into its ecosystem.

Consider how Apple’s iPhone has successfully kept its leadership position through maximizing a set of key complementors that make it harder for end-users to switch to another smart phone. With thousands of geographically distributed developers, Apple users have access to a wide array of complementary services on

Apple Store and iTunes, such as apps and podcasts. This triggers a virtuous cycle: as variety expands demand for the product (the iPhone), it also prompts an increase in the use and supply of other complementors. Similarly, Amazon keeps adding new complementors to the Prime Membership basket to strengthen its competitive advantage.

- Firm’s role

There are two main roles a firm can play in an ecosystem. They can be an orchestrator or a partner.

An orchestrator needs organizational, managerial, and cultural capabilities to align the various parts of an ecosystem while ensuring superior customer experience. Seven of the ten largest companies by market capitalization are all ecosystem orchestrators: Amazon, Apple, Alibaba, Alphabet, Facebook, Microsoft and Tencent.

While there are firms globally that can afford the required capital expenditure to build and develop an ecosystem, only a few have the appropriate capabilities and mindset to do so. The main challenges arise when the firm has to open to potential complementors – who might be long-time rivals or players in relatively unknown industries. When this happens, or when a company is too late to the game, a firm might consider playing in an ecosystem as a partner rather than an orchestrator.

A partner plays a more strategic role compared to a mere contributor, who has transactional relationships (typical of suppliers) with one or more of the ecosystem’s parties. As a partner, a firm can leverage complementarities in terms of the ecosystem’s products or services production, consumption, data, or a mix of all. Depending on the ability to position the firm as a unique and differentiating partner, the value that the firm can extract from the ecosystem may significantly increase.

Insurance companies are forging key strategic partnerships with multiple ecosystems. For example, there is a global strategic partnership between Alibaba, AXA, and Ant Financial Services. AXA provides customized insurance products for Alibaba’s retail and commercial customers, and travel insurance for Ant Financial Services’ customers traveling outside of China.

- Ecosystem architecture

What are the connections and relationships with other parties necessary to make the ecosystem work? These should cover customers, partners, and other players, such as contributors and suppliers. No party should be left out of the ecosystem’s architecture.

Having identified its role as an orchestrator in a semi-closed ecosystem, our agrochemical client looked at the ecosystem architecture. It describes its role as providing an offering that customers can partly customize by choosing from a range of products and services. This is supported by its digital platform, which engages with farmers and collects data for further experience personalization.

An important element of an ecosystem’s architecture is the governance mechanism. The less complementarities, the more traditional the hierarchy, and therefore decisions are unilateral (made solely by the orchestrator). Similarly, the more complementarities there are, the stronger and more urgent the need for a set of standards and rules to govern the ecosystem’s complexity.

- Partnering model

Who are the partners involved in the ecosystem? What are the terms of the partnerships? There might, for example, be a shared set of standards. A company must understand the motivations of its partners in order to build and manage a superior partner network. Competition for partners is high, and orchestrators need to have a compelling value proposition to attract the best partners. Our agrochemical client has built a differentiated partnering model. With most of its strategic partners, it has entered product codevelopment partnerships. With new players, such as developers of its digital app store platform, it has defined standard agreements and rules.

- Customer relationship models

What are the information flows that will form the central nervous system of the ecosystem? Where will the touchpoints with customers be? How will we manage them and what are the potential network effects that might result?

The POSB Smart Buddy launched in 2017 by DBS, a leading financial services group headquartered in Singapore, is a case in point. Worn by primary school children as a smartwatch with contactless payment functions, the POSB Smart Buddy has offered a powerful gateway to radically increase the number of touchpoints and frequency of interactions. Along the student’s journey, DBS has developed an ecosystem of services that goes beyond pure payments. POSB Smart Buddy complements other parties’ services (such as bookstores, nearby school merchants, and the local transportation system) and key partners’ offerings (mainly education providers) to provide a more holistic experience for children. As the programme evolves, DBS continues to iterate and improve on POSB Smart Buddy’s features by leveraging the richness and depth of information flows across the various parties in the ecosystem.

- Value-sharing model

What is the economic model for the ecosystem? Compared to the profit formulas of a traditional business model, ecosystems have a higher degree of complexity. As multiple parties are involved – including strategic partners with whom to share value – the orchestrator needs to balance the revenues and costs of the ecosystem’s players with surgical precision.

For the agrochemical company the model brings increased and stabilized revenues through subscriptions

and customer insights for product innovation. For the farmers there are improved crop yields thanks to customized support and decision-making – and, thereby, reduced risks. And for the insurance companies and other commercial partners there is access to a large customer base and its data. All are beneficiaries.

All of these elements can be summarized into what we call an ecosystem canvas, a one-page tool to capture an ecosystem strategy. We have used this canvas with companies across different industries worldwide. It allows them to interrogate the reality of ecosystems, it raises the key questions that require answers if their company is to turn the concept of ecosystems into profitable reality. It aims to close the gap on the how to design and execute an effective ecosystem strategy.

Alessandro Di Fiore is the founder and CEO of the European Centre for Strategic Innovation (ECSI) and ECSI Consulting (ecsi-consulting.com). He is based in Boston and Milan.

Elisa Farri is an associate partner at ECSI Consulting (esci-consulting.com). She is based in Milan.